Dec 24, 2024

Oct 13,2024

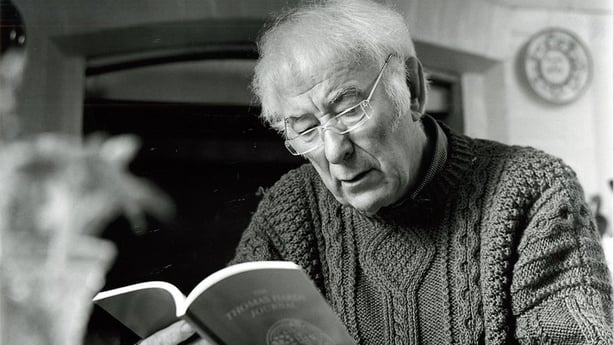

When considering an oeuvre as vast as Seamus Heaney's, what correspondences seem to offer is a tantalising glimpse behind the curated persona.

Love letters, for instance—as of those between Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West—fascinate precisely because they illuminate certain strictures within the artist’s life. In Woolf’s case, we can see the devastating effects of institutionalised homophobia and misogyny on her mental health, which in recent times has allowed for a more compassionate way of approaching her work.

With Heaney—as Letters editor Christopher Reid notes in his introduction to his acclaimed volume, now in paperback—we already think we know enough about the man to formulate an intimate understanding of the artist. 'The impression,’ Reid says. ‘Is that what has been offered for public consumption… contains within it an uncommonly generous helping of the personal.’

If we speculate about Heaney’s development during the apex of confessional writing in the 1950s and 60s, we must also deduce that he anticipated such personal readings of his work. Essay collections such as 1980’s Preoccupations and 1988’s The Government of the Tongue seem to confirm this, with Heaney waxing lyrical about the formative influence of Sylvia Plath and Robert Lowell in particular. But there is also an acute sense of the limiting nature of confessional writing, and the extent to which it fosters expectations about access to one’s private life.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Listen: Editor Christopher Reid on The Letters Of Seamus Heaney

In a scathing letter to would-be biographer Michael Parker on 12 July 1988, Heaney writes: ‘[The] shock of intrusion, which I felt when I heard of your initial visit to my family, has been dramatically renewed with the news of [your book…] If any photograph appeared, or map that gave access, I would be devastated [Moyola] is one of the most intimate and precious of the places I know on earth, one of the few places where I am not haunted or hounded by the ‘mask’ of S.H. It would be a robbery and I would have the cruel knowledge that I had led the robber to the hidden treasure and even explicated its value.’

It's a timely reminder about the nature of literary celebrity, especially given more recent trends within publishing around exploitation narratives, autofiction, and the perceived marketability of both author and work. It is instructive, too, on the nature of autobiography and the point at which a narrative about one’s life becomes the whole.

What's interesting to consider in this regard is that Heaney’s generation might be the last for whom correspondence was conducted exclusively through the medium of letters.

What we discover, for example, is that Heaney’s 2008 book of interviews with Denis O’Driscoll, Stepping Stones, was motivated by a desire to ‘keep biographers at bay’. That for all its remarkable frankness, certain doors within Heaney’s life would always remain closed, and huge swathes of his most intimate knowledge remain strictly between him and his family and friends.

This is of course as it should be, though reading Letters - as indeed anyone’s private correspondences - one can’t help but feel a renewed sense of eavesdropping. What’s interesting to consider in this regard is that Heaney’s generation might be the last for whom correspondence was conducted exclusively through the medium of letters. Email, text message, DM, WhatsApp, and other forms of modern communication would have had no bearing, and it is clear from Heaney’s letters that he enjoyed a level of confidence that communication now does not allow for.

As a medium, the letter demands intimacy and detail in a way that instant messaging does not. By comparison, most of what we say to one another nowadays might be considered scattershot, shallow and in hoc to the demands of immediate gratification. By reducing ourselves to a series of marketable data points, we have lost some of our collective capacity for refinement. We have become inured to the idea that ownership of even our most private communications is mediated by phone companies, internet service providers, social media platforms and government agencies, and consequently, we have become reluctant to commit certain things to writing.

This is not to say that Heaney’s communications would not have been monitored, or that he would not have been aware of the dangers of saying certain things. When you consider his background as the eldest of nine in a rural Irish Catholic family, with at least some sympathy for the idea of a United Ireland, it is inconceivable that a public figure of his stature would not have been monitored by British state security services at the height of the Troubles. In one particularly illuminating letter to Faber director Rosemary Goad, dated 28 April 1969, he writes: ‘We’re still short of water after the explosions and I’m almost certain that the last flat wheel I got (it was flat when I went out yesterday morning) was the work of Protestant saboteurs. You’re lucky to be out of it.’

Watch: Ciarán Hinds reads from Seamus Heaney: A Life in Letters

Even more fascinating is the footnote which Reid provides, speculating on Heaney’s reticence around committing his personal experiences of the Troubles to paper: ‘Although SH had joined a protest march against the Royal Ulster Constabulary the year before and, as a Catholic, was acutely sensitive to the sectarian divisions in Northern Ireland that would culminate in long years of bombing and bloodshed, he seldom in his letters mentions the impact on him personally. This is a rare instance.’

‘Whatever you say, say nothing’ as Heaney would later write in his 1975 collection North; for even in our most intimate conversations—be they conducted through letters, emails, or overheard snatches of conversation—someone will always seek to make themselves an audience.

The Letters of Seamus Heaney (Ed. Christopher Reid) is published by Faber.