Dec 24, 2024

Oct 13,2024

The thing about history is it has already happened. The thing about lessons is we are never done learning them. When the artist Debbie Godsell builds a round tower out of Church of Ireland kneelers - some borrowed from a local congregation; some newly made and printed with archive and other imagery, and names this work History Lesson, she is telling us both of these things, and more.

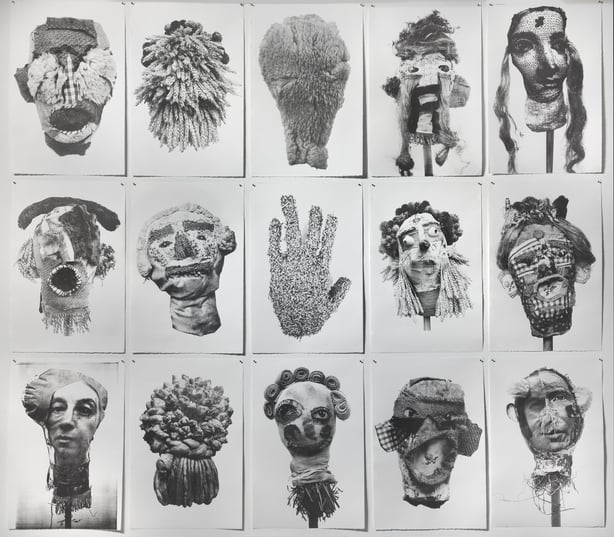

For Godsell, raised in a Church of Ireland family but no longer particularly religious, 'Flail' is an identity project. It’s about delving into a fraught, uncomfortable relationship with the past, and with the land. It is about a folklore gap, a knowledge gap, a problematic gap in our definition of Irishness. The Godsells came to Ireland in the 1640s. Godsell is an Anglo-Saxon name. The artist has been trying to imagine her ancestors’ faces. She has bought a bag of one hundred moleskins in a vintage shop. She is working with straw and fabrics found in her mother’s neighbour’s attic. She is working with new and old archive material. The resulting prints will be large, like giant mugshots, strangely poignant, oddly absurd, and unexpectedly dark.

The 1901 census recorded sixty-nine people on the island of Ireland with the surname Godsell; 39 were Anglican, 30 Catholic. The majority were farmers and living in the counties of Cork and Tipperary. For comparison, there were eighty-seven people with the surname Leach (mine, from the Old English, also Anglo-Saxon): 39 Anglican, 36 Catholic, 10 Presbyterian and 2 Methodist. Those were scattered across sixteen counties from Mayo to Dublin and Antrim to Cork and most were not farmers. Here's another fact: in 1901, Murphy (an Anglicisation of the Irish Gaelic name Murchadh) was the most common surname in Ireland. Of the 56,648 people called Murphy, 53,911 were Catholic, 1,478 Anglican, 851 Presbyterian, and the rest (408 people) Methodist, Baptist, Plymouth Brethren, Christian, Protestant, Brethren in Christ, Independent, Church of Christ, Mormon, Quaker, or religion not given. There were Murphys in all of the thirty-two counties, and the majority of them were farmers. The entire population of the island was 4.46 million. What does it mean to be Irish?

Godsell's tower contains photographic images of harvests reproduced from the National Folklore Collection; printed images of snakes and Saint Patrick, that icon of Irish Christianity claimed by both Protestant and Catholic; images from the early 1900s 'Big House' Croker family photo album held in the Cork City Archives; and military epaulettes and other printed compositions incorporating an enlarged image of the artist’s eye. Post-colonialism and decolonisation are urgent themes in 21st century contemporary art. Godsell, born in, belonging to, and of the Republic of Ireland declared in 1949, asks what happens when as an artist, ancestrally-speaking, you come from the other side? "My own family history is of planters," she says. "I have had to figure out what to do with that."

The roof of her History Lesson is made from handwoven oats. Her tower is soft and verging on unstable, like a childhood construction of domestic cushions, supported by timber struts. History Lesson had previous in-progress titles: Babel Tower, Round Tower, Knowledge Gap, Dora Casserly. The last is the name of the Dublin school teacher whose History of Ireland books were published by the Educational Company of Ireland in 1941 and used widely in Church of Ireland national schools through the 1940s. Post-independence, this former colony had the opportunity for the first time to depict its coloniser in the school books used to tell Irish history to Irish children. The books used in the majority Catholic schools were not considered appropriate for Irish Protestants. Godsell describes round towers as one of the few non-contested things in the school history books when it comes to how the past was taught to us children of the Republic.

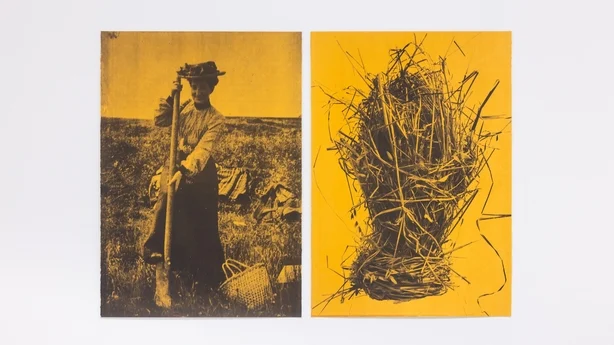

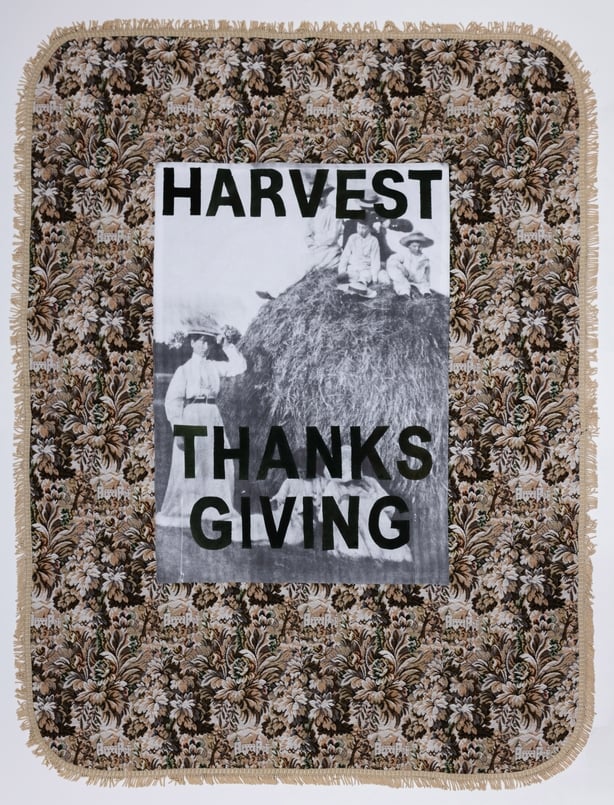

For those for whom religion is primarily an important cultural identifier of difference, this work may be read as proving that point. But history changes in the now. At Cork Printmakers where an early iteration of Flail was shown in 2023, Godsell spoke of a quality or phenomenon she refers to as "quietism", a type of silencing. She says it means "don’t bring things up from the past", and she believes it led to a certain cultural reserve among Irish Protestants in the Irish Republic. Her current work, which began with a project to photographically document the Church of Ireland Harvest Thanksgiving altar and church decoration tradition, is part of a deliberate move on her part to resist that.

Historical records show the ascendency class was a very small proportion of the Irish Protestant population. The "ordinary" folk were more numerous than the "Big House" folk, and also more silent, culturally and socially. Is "quietism" a kind of stoicism? Is it a way to stay safe? Is it a way to apologise for taking up space, for still being here? The kneelers, now part of History Lesson, include the printed words, "Don’t make a fuss" in an Anglican Gothic font. A flail is a threshing tool, used at harvest-time. To flail someone is to hit them many times. To flail is to make a big movement, a noise, a fuss.

Godsell found a scaffolding on which to hang her artist tools in the work of ethnologist Deirdre Nuttall, a potential support structure through which to begin to navigate the territory ahead, and behind. That territory includes a history of othering and otherness, but also a kind of validation, that Godsell was right to feel a persistent unease. The everyday traditions, folklore and heritage of Irish Protestant people had been demonstrably excluded from the record. The 1930s Folklore Commission operated on narrow ideas of who the folk were: rural, Catholic, poor. There was a dismissal, or neglect, of Protestant Irish folklore, even among the material gathered in copybooks by Irish schoolchildren for the 1937 Schools Project. In donating more than 140 documentary photographs of West Cork Harvest Thanksgiving Festivals to the National Folklore Collection, held at UCD, Godsell moved to fill a gap.

Stereotypes, myths and superstitions about Irish Protestants in the Irish Republic have ranged from the whimsical to the profound: that the Banshee doesn’t come to Protestant homes, that the Famine only affected Catholics, that Protestants farmers dig with their left foot. Godsell’s Digging with the left right left right left is a repurposed sleán, a two-sided spade used for cutting turf, with added extra oak footrests. Here are prejudices and presumptions made visible, and ridiculous, as physical outcrops on an old wooden shaft. Godsell says her work is less about faith-based and more about cultural identity. For her, it is about community and place. It is about customs and traditions beyond notions of God, and an investigation of relationships with the land.

The Harvest Thanksgiving tradition which began in 1840 in the UK, was not adopted in Ireland until around 1900, because of the Famine which began in 1845. The phrase itself resists easy translation to Irish. Altú an Fhómhair combines the word for grace, a moment of gratitude before meals, with the word for autumn. Altú an Fhómhair implies something much more than a religious ritual enacted by a particular set of church-goers on the first Sunday in October. The tradition of a harvest festival as part of farming culture has echoes and resonances worldwide. In Ireland, it was traditionally called Lúnasa and began around 1 August. There was particular significance associated with the cutting of the powerful last sheaf, known as the Cailleach (wise old woman or hag), which would be brought home and carefully stored for good luck.

When Godsell began to work with a local farmer on this project, she asked him to leave enough of the end of the harvest so she could bind a last sheaf of oats. A profound and unexpected sense of connection came from that one act: to the land, to nature, to the planet, to all of humankind who must produce or seek food and harvest it to survive. It was an action that felt ancient, communal, universal, and an action surely complicated again by her descendancy from Irish planter stock. Back in the studio, her imagined ancestors became the Protestors, a series of ten prints. She gave them names, and jobs: Edward, Land Steward; Suzannah, Farmer; John, Skinner; Daniel, Settler; Amos, Farmer; James, Gentleman; Elizabeth, Queen; James, Carpenter; Ann, Servant; and hidden among them, God’s Almighty Hand.

A key research image for Godsell has been a painting by the Irish watercolourist and world-traveller, Beatrice Gubbins, who lived at Dunkettle House in Cork. This idyllic, harvest scene hung in Godsell’s grandmother’s home, a reminder she says, that "it goes back to the land all the time". Who gets to treat the landscape as playscape and visual salve? Who actually labours on the land? Her Harvest Thanksgiving, digital print is an imagined last altar, a photograph arranged in the tradition of a classical still life painting, laden with symbolic items: Godsell’s granny’s minks; vegetables from a church altar display; a decorative pineapple, the ultimate status symbol of the British imperial project; preserved goods, taxidermied creatures, and mouldy bread. Symbols and pointers to other meanings pop up elsewhere in this work. Thrash, a timber-frame installation which echoes the structure of an old threshing machine, is threaded with a ream of printed grain, and contains Jesmonite-cast apples, sliotars, turf and potatoes. Repurposed fabrics speak to the Protestant make-and-do mentality Godsell grew up with.

This work represents a slow movement towards and into her own relationship with difficult ideas about belonging and estrangement from community and place. From investigations in, and new contributions to, the archives, she has begun to move closer to more intangible subjects like multigenerational learned behaviours, use of language, and even tricker, feelings associated with post-colonial legacies, including shame.

A kneeler is a hassock, to cushion the knees while praying, and it is also a clump of matted grass in marshy or boggy ground. The kneelers in Godsell’s work are building blocks of identity. They are an everyday material object that, growing up, she never realised didn’t exist in Catholic churches. "I didn’t know they were unique," she says, "I thought everyone had them." She means all of us Irish, here, everyone, living on this island together.

The footage for her three-screen video Flail, was recorded at a farm in Cork in August 2023. The artist began, standing, with her palms open in a gesture of surrender, humility, welcome, openness, peace. She began too with ten sheaves of oats, with a threshing stone on a wooden stool with three legs of silver birch, with a sheet to catch the grain, a flail, a sieve, and her own physical, emotional, and psychological energy.

The threshing takes about fifteen whacks per sheaf. The stone remains improbably immovable on top of its short legged, makeshift, portable, sturdy seat. She calls it a visiting stool. "It’s a seat you made for yourself, if you went visiting and there was nowhere to sit". A flail is an unwieldy, almost unpredictable thing, a wooden baton loosely attached with a leather thong to the end of a longer wooden stick. It moves with the unpredictability of a double jointed elbow. The action of hitting, flailing, whacking, beating the grain is intense, organised, repetitive. There is a rhythm required to do this job well, a revisitation of every action with another one laid on top. In the building violence of it there is an acknowledgement of the cycles of nature, the labour of creation, gestation, and something else. "There is a well of historical grievances coming up through me," Godsell laughs afterwards. Perhaps from both sides. As she sieves the hand threshed and flailed oats, the chaff floats up on the wind, then slowly the heavier waves of rich grain spill in repeat cascades over the edge of the wooden circular sifter with its metal grid base. "I am beating myself into history," she says, "beating myself into the gap".

Debbie Godsell: Flail is at The Source Arts Centre, Thurles, County Tipperary until Saturday 19 Oct 2024 - find out more here.