Dec 24, 2024

Oct 11,2024

Michael Dempsey, Head of Exhibitions at the Hugh Lane Gallery, introduces La Grande Illusion, a major exhibition of works by internationally acclaimed artist, Brian Maguire, now showing at the Hugh Lane.

La Grande Illusion appraises Maguire's activism in human rights, and his ongoing efforts to document the shape-shifting nature of war with its far-reaching impact on the poor and our environment.

Read the inhumed faces of casualty and victim (*)

When the work we do becomes a means of mere survival rather than one of creative fulfilment, we experience what Marx called alienation. Art in its commodification is also wrapped up in this alienation, unless it is an art that occupies a space of difference, a space that is absolutely essential to a socio-political culture of equality. This space is where the relations between the bonding elements of a society are suspended, neutralised or resisted. As curators of cultural institutions we hold on to this ambiguity, its agonistic challenge. Our involvement extends beyond the purely logistical aspects of exhibition production and we acknowledge that it can and does influence the narratives and interpretations of artworks. This awareness feeds into the larger responsibility of how museums are programmed – either reflecting collective memory already existing or actively shaping visual narratives of identity.

In the context of contemporary capitalism and the increasing reliance on coded algorithms for monetising subjectivation, a museum can be utilised as a heterotopic space. Michel Foucault's concept of heterotopia refers to spaces that exist outside of normal social and cultural order, challenging established norms and serving as sites of alternative realities. These spaces are often associated with resistance, as Cuban artist and activist Tania Bruguera has recently shown in a project about censorship titled The Condition of No at the Museum Villa Stuck in Munich. Critical engagement with the world can be encouraged by curating exhibitions that offer diverse perspectives, alternative histories or marginalised voices. It can disrupt the dominant discourse and encourage critical thinking through our institutional programmes. In prompting these questions as cultural producers and consumers, we can reflect on our own roles within these systems.

The dilemma of new institutionalism is how to respond to artistic practice without prescribing the outcome of engagement; how to create a programme that allows for a diversity of events, exhibitions and projects, without privileging the social over the visual. – Claire Doherty

Opening up a dialogue that pulls into the foreground that which has been sidelined, repressed and discarded is a gifted opportunity for visualising such diverse perspectives. Museums are generally thought of as warehouses of heritage, but they can be reimagined and activated through the exhibition form as spaces of persistent research. La Grande Illusion develops Brian Maguire’s multilayered oeuvre by transforming the galleries of Hugh Lane into a space for action and dialogue. Creating vectors for the themes Maguire so doggedly mines, the exhibition illuminates the many traces of historical violence that connect the contemporary politics of land, history, body and identity.

'The fact is every war suffers a kind of progressive degradation with every month that it continues, because such things as individual liberty and a truthful press are simply not compatible with military efficiency.’ – George Orwell

The German philosopher Walter Benjamin observed that there was an aesthetic dimension in the political and also a political dimension in art. Brian Maguire is an artist who shifts between these two dimensions and his courage transcends the linear presumptions on which modernist and postmodernist practice are based. He has negotiated the needs of ‘the social’ as well as ‘the aesthetic’. His methods are comprehensively expressed by other authors within the catalogue that accompanies this exhibition, so I will concentrate on how paintings provide a more permanent record of human history and culture in an age where digital content is fleeting.

Benjamin argues in his seminal essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ that the ability to mechanically reproduce artworks fundamentally changed their function and meaning. Their reproducibility alters how people perceive and interact with images. Art became more democratised as it was no longer tied to a single place, like a museum, nor a single elite class; instead it was disseminated and experienced by the masses through various media. But Benjamin was more subtle when it came to his concept of ‘aura’ in a work of art. He notes that it tends to disappear in favour of ideology with the advent of reproduction (photography and film). In our age of supercharged digital reproduction and news feeds, should we reappraise the aura in a viewer’s relationship with an artwork? Our altered perceptions may have reached saturation point. As our screen monitors deliver countless images in our lives, we have become habituated in offloading our memories of events and stories to our digital clouds and databases. Images of human tragedy are ‘framed’ so as to prevent us from recognising the people portrayed as living fully ‘grievable’ lives, i.e. lives that we can identify our own lives with. So we offload them. As the construction of memory undergoes another radical shift, our relationship to images and the visual arts is also transformed.

For every image of the past that is not recognised by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably, wrote Benjamin of recollection and I am reminded of George Orwell’s warning that "Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past".

Watch: Brian Maguire in conversation, circa 2023

La Grande Illusion is an exhibition that plays with our ambivalent attraction towards the flow of digital images we encounter daily. News stories that have slipped into oblivion emerge throughout Maguire’s paintings like ghosts haunting the present. They punctuate our memories, charged with meanings that might not fully appear to us – collapsing present and past, his images of violent acts resonate through the gallery space as beacons of recollection reminding us that the zones of chaos, however far away they seem, do affect us in this globalised world.

Six themes are laid out in a visual narrative, reminding us that art history always reflects structures of domination. It puts the power inherited by the museum to good use by displacing motifs usually linked to history’s victors in favour of other genealogies.

The paintings of Brian Maguire play a critical role in critiquing, complementing and providing an alternative to state narratives, and the exhibition offers a space for ideas and emotions that may be overlooked or underrepresented in the fast-paced digital world. Here I again draw upon Walter Benjamin, who argues that the painting invites the spectator to contemplation, whereas in the moving image (I include the ‘swipe’ action of social media here) the spectator cannot abandon himself to his associations. No sooner has the eye grasped a scene than it is already changed. Thoughts are replaced by moving images – Walter Benjamin.

Europe’s Optical Illusion is a book by Norman Angell, first published in the United Kingdom in 1909, which has been influential in the field of international relations. Angell’s primary thesis was that war was economically and socially irrational. But this theory did not take into account the economic benefits of overseas conflicts that extended in the 20th century to the arms-producing countries. By supplying arms, the producing country could influence the outcome of conflicts, shaping global geopolitics in ways that favoured its economic and strategic interests. This is no illusion, and so we expanded the exhibition reference to Jean Renoir’s eponymous film La Grande Illusion (1937) in which human solidarity is demoralised by class in a World War I prison camp.

Maguire’s humanitarian work draws on this solidarity and his persistent response to the omnipresent violence experienced globally enables Maguire to engage the aesthetic practice of art in allowing testaments to be revealed. Alongside media reportage and judicial processes, his work uncovers the complications in bearing witness. In doing so, Maguire jostles at the boundaries of what constitutes truth. The work in this exhibition draws us not only towards questions of what are evidence’s presentational circumstances and conditions of use, but also towards questions of who is represented in these spaces and what kinds of images can and cannot be seen or remembered.

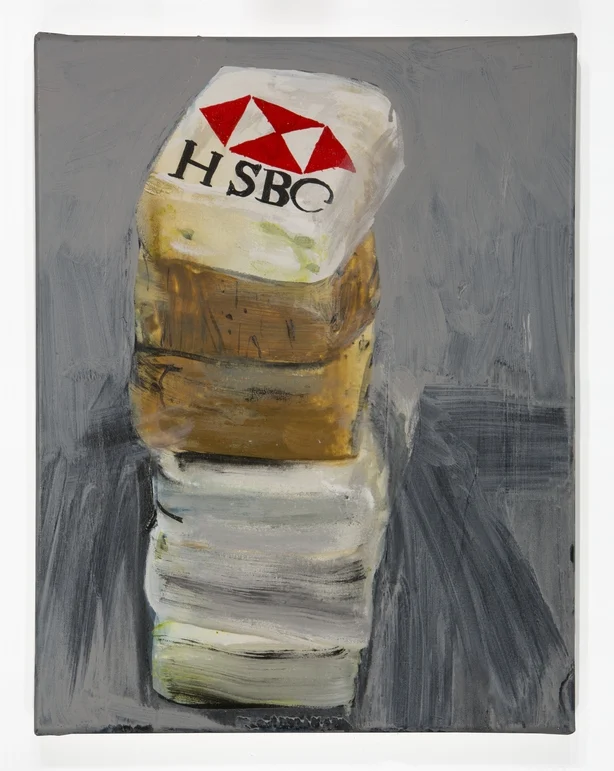

Integral to understanding violence is the testimony of opposing sides before any reconciliation is to be achieved. Whether it is a Mexican drug feud (Nature Morte, 2014), vulture capitalism (Contemporary Ruin, 2010), colonial legacy (Fake News, Mr William Earles, Sudan 1880, 2018) or a refugee camp (Bentiu Camp South Sudan 1, 2018), Maguire’s peripheral vision, whereby he connects the act of love with the act of looking, captures harrowing and ongoing cycles of human and environmental tragedies. Bringing them to our attention in his paintings is an act of love.

It takes great courage to see the world in all its tainted glory, and still to love it. – Oscar Wilde

In a new era of extreme inequality that has derailed democratic progress since the 1980s, the reaction is a drift toward the politics of ideology. It is the fruit of ignorance and intellectual specialisation and there is now more than ever the necessity to link the present to the past, to connect contemporary artists with historical events and figures.

Brian Maguire combines biographical elements with global political issues, and museums can play a crucial role in shaping a more diverse, inclusive and critical cultural landscape. This continuity is essential for understanding the evolution of human experience.

La Grande Illusion is at The Hugh Lane until 23rd March 2025 - find out more here.