Dec 24, 2024

Dec 20,2024

Analysis: Associating Christianity and Catholicism with Irishness was a mark of distinctiveness for the Irish Free State in its early years

By Billy Shortall and Angela Griffith, TCD

Through their work across time, Irish artists have recorded and expressed all aspects of human life, including the ideas and dreams of the individuals who made it, and the agency and beliefs of the societies that they served.

Sometimes artist and society clashed. For example, the early abstract paintings of modernist artist Mainie Jellett were described as 'sub-human' by artist and critic George Russell in 1923. Jellett found a greater acceptance for her work after she introduced religious references and subject matter, and this enabled her to converse about modern art with a sceptical public through radio and other media.

During the 1920s and 1930s, as the Irish Free State began its journey after Independence, the Government selected art works for exhibitions at home, such as the Tailteann Art Exhibitions, and abroad in Paris, London, and Chicago that presented a positive image of its inhabitants and counteracted the negative, clichéd cartoon of feckless Irish people, favoured by the British press.

Artist Paul Henry's West of Ireland landscapes and Jack B Yeats’ scenes of everyday Irish life gave a positive view of Irish people in their own place and showed a functioning State, helping to define Irish identity. The Ireland that emerged in 1922 had a predominant Catholic population, and devotional imagery of the Sacred Heat, scenes from the Holy Land of the nativity, and the life of Jesus and his mother Mary were conspicuous in homes as well as in Churches.

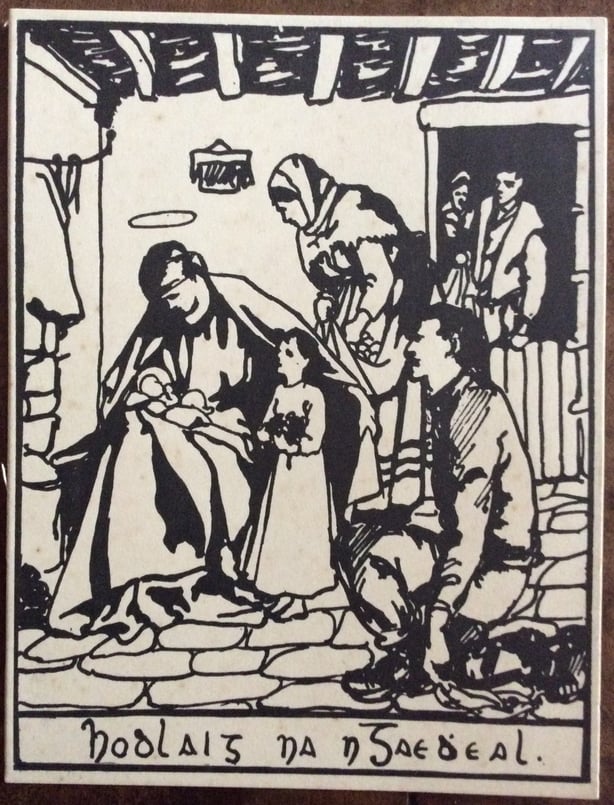

These religious images often took on a particularly Irish flavour. Beatrice Glenavy's hand coloured print and card, Mother of God, for Cuala Press presented a domesticated and Gaelicised image of the Virgin Mary with her sleeping red-haired Christ child in an archaic Irish cottage interior. Mary irons and gently admonishes two country angels to be quiet. The window frames a distinctive Irish landscape.

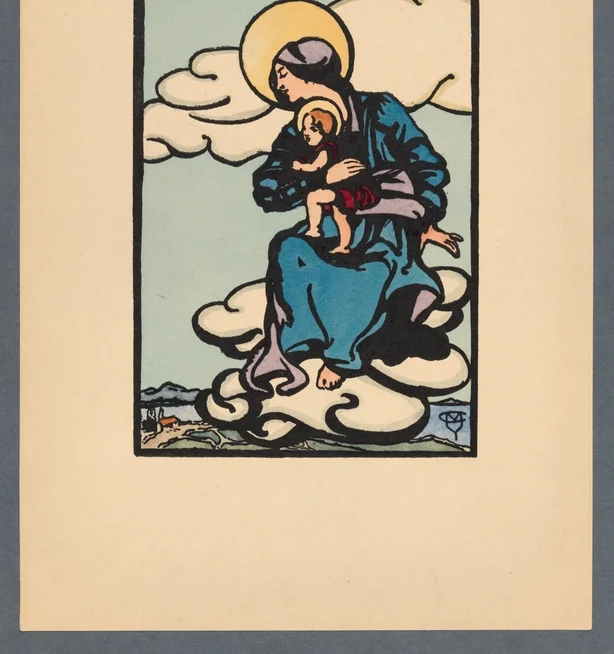

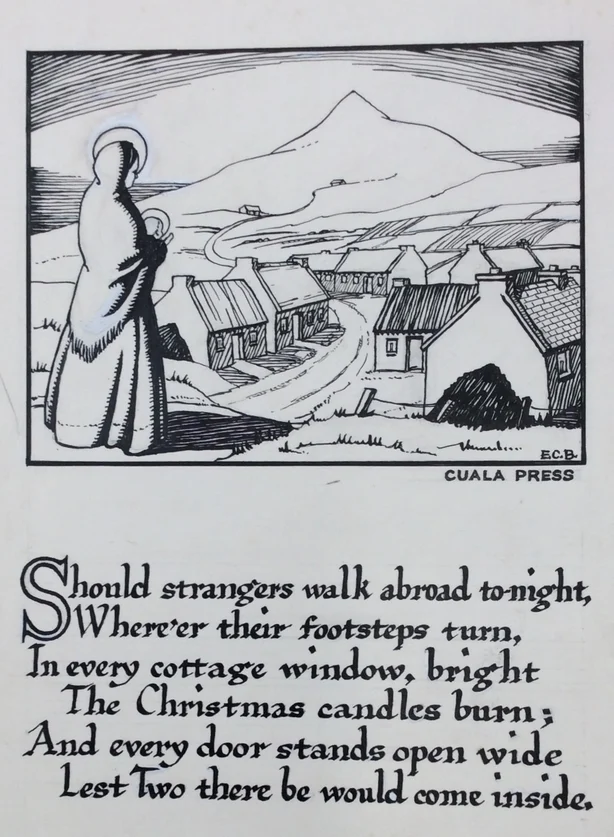

Other Cuala Christmas cards also Gaelicised religious scenes for prints and cards. Mary Cottenham Yeats' Cuala image of The Virgin and Child shows a similar red-haired Christ in an Irish setting, and Eileen C. Booth’s Christmas card showed a Madonna figure standing guard over a west of Ireland village.

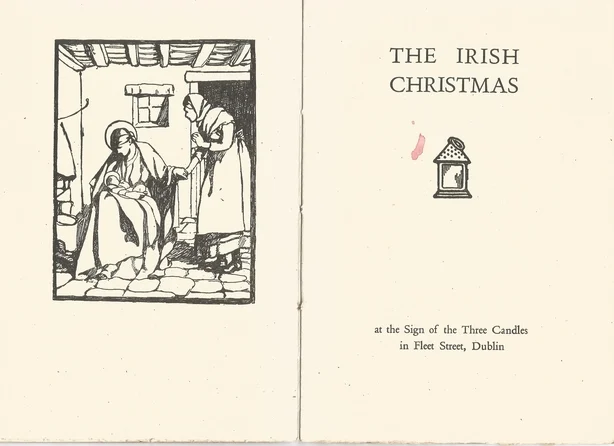

The Irish Christmas, a poetry miscellany by Colm Ó’Lochlainn’s Candles Press, first published in 1917, its third and last edition was in 1933, contained illustrations by Margaret (Daisy) O’Keefe and a frontispiece specially designed for the book by Sadhbh Trinnseach, of a haloed Madonna and Christ Child in a simple Irish cottage interior being assisted by a local woman in a headscarf.

Trinnseach herself was born Frances Georgiana Chenevix Trench in Liverpool in 1891, however she developed a love for Ireland, became an Irish nationalist, adopted an Irish-Irelander or Gaelicised identity, and involved herself in the movement for Irish independence. Despite dying aged only 27 of the 'Spanish flu' in 1918, her portrait of Eoin MacNeill was selected for exhibition along with both Glenavy’s and Cottenham Yeats’ Irish Madonnas in an Irish government selected exhibition of Irish Art held in Paris in 1922.

The acme of Catholic Ireland devotion expressed itself in the 1932 Eucharistic Congress. It was the largest spectacle ever held in the Irish State, over a million people attended mass in the Phoenix Park. The Congress was a curious mix of the modern - the elaborate communications, lighting, and infrastructure required for staging an international event - with the traditional nature of the proceedings.

In 1934 a framed print of a West of Ireland Madonna was presented to Pope Pius XI in the Vatican as a memento of the Congress. Titled, The Blessed Virgin Mary, Queen of Ireland, it was a representation of Mary and Jesus but within an Irish idiom.

Based on a painting by artist Leo Whelan and reproduced in an edition of about 200 mostly signed colour prints, this Irish-Ireland image rhymed with both the Irish Catholic Church and political establishment. Identifying the Madonna with real Irish people placed in a local landscape - the infant has a ruddy complexion and red hair; the Virgin is in Irish attire. Whelan’s models for the Blessed Virgin and the infant Jesus were locals with a connection to the artist. The infant was reputed to have been modelled on artist Sean Keating’s son, Justin, who would later become a Minister in the Irish government.

For a new State announcing itself to the world and seeking to assert its own unique identity, associating Christianity and Catholicism with Irishness was a mark of distinctiveness. For the artists whose personal ideologies usually dovetailed with the political, this work was profitable. Halos and headscarves sold well.

Cuala Press Prints are available to view as part of the Virtual Trinity Library at digitalcollections.tcd.ie and a Trinity College reconstruction of the 1922 Paris Exhibition of Irish Art funded by the Decade of Centenaries programme is at www.seeingireland.ie. Dr Billy Shortall and Dr Angela Griffith both worked on the TCD Cuala Press Project.

Dr Billy Shortall is a Ryan Gallagher Kennedy Research Fellow Fellow at the Irish Art Research Centre (TRIARC) at the School of Histories and Humanities at TCD. Dr Angela Griffith is Director of the Irish Art Research Centre (TRIARC) at the School of Histories and Humanities at TCD. Both are undertaking new scholarship on Cuala Press prints, as part of the Cuala Press Project, Schooner Foundation 2020-2023