Dec 24, 2024

Dec 18,2024

Analysis: There may no obvious traces of Ireland or Irishness in Bacon's work, yet his studio now resides in the heart of Dublin

The artist Francis Bacon is one of the most recognised names in contemporary art and modern culture, whose paintings command record-setting prices and exhibitions of work in major galleries around the globe. Born at 63 Lower Baggot Street in Dublin in 1909 to English parents, the location of Bacon's early life in Dublin would come to be seen in later years as its cultural heartland, earning the moniker of 'Baggatonia', with its plethora of musicians, pubs, theatres, and artists.

But Bacon is not so readily recounted in that Baggatonia history, or within the common cultural discourse of ‘modern Irish artists’. He moved from country of his birth when he was 16 years old, so how is Bacon remembered today in Ireland and, indeed, is he, or can he be, considered an Irish artist?

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

He has been referred to and listed as a British artist for the majority of his life and career and revered as an icon of 20th century British culture. Yet aside from his works which populate the walls of major galleries and are prized by wealthy collectors, Bacon’s greatest legacy is his artist's studio which now resides lock, stock, and paintbrush in the Hugh Lane gallery in the heart of Dublin city.

Leaving the hustle and bustle of O’Connell Street and Parnell Square, visitors to the gallery will find artworks by modern and contemporary Irish and European artists, from Claude Monet to Sarah Purser to Sean Scully. All of this builds on Lane's original vision and bequest for a Dublin municipal gallery to house a range of modern art for the city of Dublin.

Beyond the main galleries, a long corridor leads you to a wall with a window and curious tubes with wide-angle lenses, like a camera’s viewfinder. This transports the viewer from Dublin directly into Bacon’s London studio of the 1960s and after, and into the world and imagination in which he painted.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

The studio was donated in 1998 to the Hugh Lane Gallery by John Edwards, Bacon's sole heir and longtime companion. Curiously, and perhaps in an act to 'claim’ Bacon as Irish and recognise his Irishness, a plaque was unveiled in 1999 on the wall of 63 Lower Baggot Street by then Lord Mayor of Dublin, Mary Freehill. The executor of the Bacon Estate, Brian Clarke, declared at an event after the plaque unveiling that "all Francis’ working life had its genesis here in Dublin".

The work to move and reconstruct the studio in Dublin involved the painstaking process of cataloguing every single item (over 7,000 items which today comprise the Francis Bacon Archive at the Hugh Lane) within the space, including its structural features. That task alone revealed the discovery of over 100 sketches, 1,500 photographs and 200 manipulated images, all laying within the maelstrom of Bacon’s frenetic and chaotic studio space, as well as over 100 slashed canvasses. The slashed and cut canvases were not a surprise to find as Bacon once said "I usually like a canvas when I finish it, but the more I look at it the more dissatisfied I become. If someone doesn’t take it away from me within a few days, I will probably destroy it".

Items within the studio revealed how Bacon used every facet of it as an all-encompassing palette, figuratively, in the detritus of pages, sketches and cuttings that littered the space, but also literally as the wooden door of the studio was covered in paint samples. A Japanese gallery offered £2 million for the door of the studio alone. Those items alone were deemed to be such value and insight into Bacon's process they represented an archive of form and work in development.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Birth alone can be less useful when looking to assess someone’s identity and cultural outlook. The artist, Jack B. Yeats, for instance, was born in London in 1871, but is rarely, if ever, described as anything other than an Irish artist. His works are highly acclaimed while depicting an ethereal, often dream like vision of Irish landscapes and wandering figures, from Dublin beaches to the Sligo coastline, as well as more raucous scenes from of horse races, boxing matches, circus, as well as Dublin streetscapes, including of course his Olympic medal winning painting, Liffey Swim (1923).

There are no such obvious traces of Ireland or Irishness in Bacon’s work. Having left Ireland as a young teenager for London, Bacon later travelled to Berlin, Paris and regularly to Morocco. In 1961, he established a base in a Kensington mews in London, where he would live and work primarily until his death in Spain in 1992.

Bacon’s life in Ireland ran in tandem with much of the violence and political and social upheaval of the Revolutionary period in the early 20th century. While born in Dublin city, Bacon’s childhood was spent largely in comfortable 'Big House’ existence in Co. Kildare. It was a period when Ireland was finding its own identity after rebellion, a war of independence against British colonialism, a civil war and the emergence of a new Free State firmly guided by the authority of the Catholic Church.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

In Revelations, their biography of Bacon, Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan indicate that these years of violence and trauma contributed to Bacon’s own dislocation from the country in later years. They also led Bacon to recognise himself as an outsider - a young homosexual man and son of a British army father with who he had an often difficult relationship.

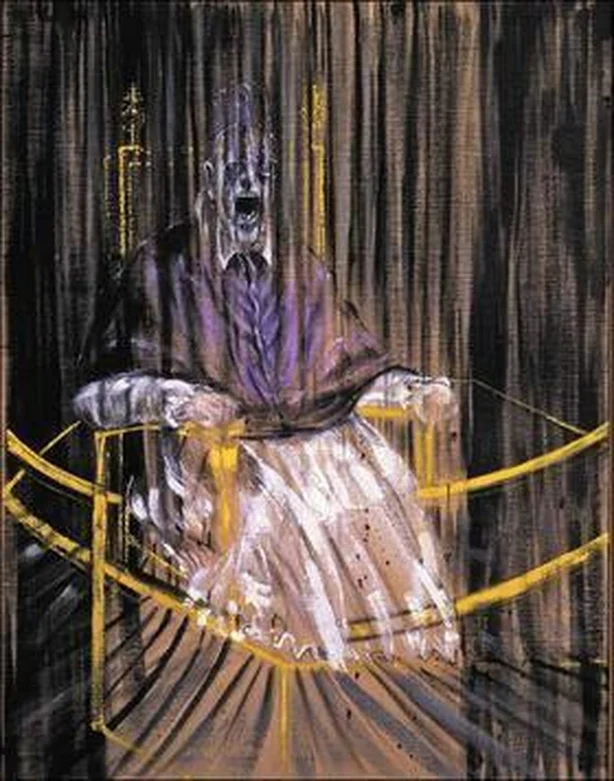

Works like Bacon’s breakthrough Study after Velazquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1953), depicting a screaming seated pope, takes an image of religious and turns it into a disruptive force of energy being unleashed. It also unsettles the Catholic iconography of the Ireland of his birth, where images such as the Sacred Heart found its place in many Irish Catholic nationalist households. It also brings to mind images of death and sacrifice of a nationalist and mythological form, as in the statue of CúChulainn depicted wounded and dying by artist Oliver Shepherd, which still stands in the GPO in Dublin today as an image representative of the blood sacrifice of 1916.

Bacon’s screaming pope and the imagery of the mouth (which he said fascinated him ever since he read a book about diseases of the mouth) is reminiscent of the disembodied mouth of an unseen narrator in Samuel Beckett's Not I (1972). Bacon spent much less time in Ireland compared to some other Irish cultural figures that in their lifetime were also often more associated with Great Britain or Europe, such as Beckett, George Bernard Shaw or Elizabeth Bowen. In life and legacy, Bacon has not had the hyphenated ‘Irish-’ attached to him in any great measure. His own antipathy towards the country of his birth also contributes to this continued sense of ‘outsider’ in his home city.

Ireland also has no blemish-free record of protecting its artistic and cultural heritage. The lack of intervention by the State to secure for Ireland the entire Yeats Family collection, auctioned by Sotheby’s in 2015 and which was split between Irish and international collections and venues around the world, is one damning example.

Yet the preservation of Bacon’s London studio in the late 1990s and its relocation to Dublin and the Hugh Lane Gallery was a cultural coup that any major gallery (or city) would be jealous of. Whatever the Irish credentials or perception of Irishness of its protagonist, the Bacon studio is a remarkable legacy for one of the world’s most influential artists, who was born in heart of Dublin’s Baggatonia.