Dec 24, 2024

Dec 07,2024

What does the recent trajectory of the arts in Ireland – from Arts Council funding increases to the Basic Income pilot – mean for musicians? How can we further strengthen music across Ireland? And what do these developments mean for the tradition of the Irish harp? Journal Of Music editor Toner Quinn reflects on the current state of the music scene in Ireland.

It is now ten years since I submitted the Report on the Harping Tradition in Ireland to the Arts Council in October 2014. Commissioned by the Council, it was a 96-page report with 14 recommendations for the future of the instrument in Ireland.

In this essay, I want to briefly discuss what happened after the report was published, and then broaden out the discussion to explore three developments that I think have the potential to affect the future of Irish music in a positive way, but none of which we can take for granted.

The harp document was not the first state report I was involved in. It was preceded by the report of the Special Committee on the Traditional Arts, Towards a Policy for the Traditional Arts, in 2004. This was a major policy shift by the Arts Council and for the Irish state. As with the harp report, what we were trying to do was show the many different components that go into these music scenes. There is an idea in Ireland that music 'just happens’ – like the weather in the sky or the grass coming up from the ground – but, as everyone in Irish music knows, there is a huge community effort that goes into making music in Ireland ‘just happen’. In those reports, we had to demonstrate that, and win the argument for support.

The combination of those two reports, I can see now, ten and twenty years on, was an extraordinary opportunity to move the Arts Council’s understanding of traditional music forward in a significant way, and in a relatively short space of time, when things were not quite as bureaucratic as they are today.

I was thirty when I was writing the first report, forty when I wrote the harp report. Now I am fifty, not working on a report, but writing more than ever about Irish music – because there is so much to write about.

Reflections

When I was asked to reflect on the ten years since the harp report for the Harp Ireland/Cruit Éireann Annual Lecture on 17 November, I had to think hard. What had I learnt over the past ten years, and twenty years, and even twenty-five years of writing about music in Ireland? I must have something concrete to say. When you run a music magazine, of course, everything comes across your desk – all the reports, announcements and press releases, as well as all the news from musicians – and then there are all of the private phone conversations that you can’t repeat. There is so much happening that it can take time to perceive a pattern.

But I have learnt firstly – and this will be of little comfort to you – that when it comes to music and the arts in Ireland, it is usually not going to develop the way you thought it would. And there are genuine, even positive, reasons for this. Irish music is such a dynamic scene, with new ideas and talent coming through all the time, bringing new demands and perspectives, that things are going to change rapidly. This disruptive energy makes it difficult for any state department or arts organisation to react fast enough, so I understand that challenge.

At the same time, state departments and organisations often have their own plans for the arts, and they can get excited about them and invest heavily in them, regardless of whether anybody in the arts requested them or not. The most recent example is the Space to Create initiative from the Department of Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, which now appears to be unsuitable to meet the needs of musicians, as pointed out by composer Sebastian Adams after the Unit 44 venue run by Kirkos Ensemble in Dublin announced that it was closing down. Space continues to be a key issue, and the seven main political parties have included it in their manifestos for the upcoming election, but their ambitions lack detail. The danger is that music will end up with unsuitable initiatives, and politicians feeling that they have done something.

Music education is also a pivotal issue, and there has been significant progress outside of schools with the development of Music Generation nationwide, but there needs to be progression after education, which is what I want to focus on in this essay.

The harp since 2014

The general picture, therefore, is of a lot of competing priorities and perspectives in music in Ireland, and the situation sometimes benefits artists, and sometimes not.

What is interesting about the harp trajectory, however, is that there has been some extraordinary progress, and the credit here has to go to the harp community and Harp Ireland who have seized the opportunity of the report recommendations. The Arts Council, of course, supported them, but it was a community movement – and a powerful community movement at that.

One of the key recommendations of the report was that the various harp organisations would come together and establish an Irish harp forum – an umbrella group – and Harp Ireland/Cruit Éireann was established in 2016, just two years after the report. In bureaucratic terms, that is lightning speed.

Another great achievement came three years later in 2019, when a campaign led by Aibhlín McCrann and Harp Ireland achieved UNESCO status for Irish harping. This thousand-year-old tradition was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. It not only raised the profile of Irish harping – it was in all the media here – but it also gives the Irish harp a layer of national and international safeguarding that can protect it into the future. That was an extraordinary achievement, and pursuing that objective certainly wasn’t one of my recommendations.

Another area where things have really changed is in the national profile of the harp. When I was researching the harp report, the diversity of the scene jumped out at me. There were so many sides to it because the tradition is so old: modern Irish harping, early Irish harping, different techniques, contrasting repertoire, experimentalism, differing opinions. I loved the energy and the jostling. It was a real strength because it made harping a living tradition. But despite all the differences, there was one point on which everyone was in agreement ten years ago, and that was that the low profile and outdated image of the Irish harp was a barrier to progress – the old cliché of the Irish colleen playing in front of a thatched cottage. Everyone in harping agreed this image was a stumbling block towards the instrument’s future, and that it didn’t reflect the reality of the exciting scene that we had.

For harpers, this was encapsulated by the fact that the instrument wasn’t included in Riverdance, and neither was it incorporated into the Ceiliúradh concert in 2014 at the Royal Albert Hall when President Michael D. Higgins made his state visit to Britain.

Things have changed however. Two recent examples illustrate the profile that the harp now has. In 2022, Bono toured his new memoir, Surrender, in the United States and Europe. There were just three musicians on stage with him, and one of them was the Derry harper Gemma Doherty from the band Saint Sister. He performed an extract from the book and the song With or Without You on CBS to two million people, and seeing the Irish harp at the centre of the performance with Bono seemed to symbolise the new era we are in.

At one point, Armstrong states that Irish harping was ‘the high point of Gaelic musical culture for over 900 years’ and Creedon says that there is ‘something regal’ about the instrument. It feels to me that the harp is gradually regaining an element of its historical status in Irish society. As Armstrong said in the programme, in a Gaelic court, the harper was the third most important person after the king and the poet.

The harp is also rediscovering a certain political status. In the movement for reunification of the island, the organisation Ireland’s Future is using the harp as its logo. It is one of the symbols that the two communities in the north share, because it is on the flag of the British royal family and it is the symbol of the President of Ireland. If there is reunification, I would not be surprised if the harp is part of the symbolism. I wonder how the harping community will feel about that and what it would mean for the instrument.

A basic income for the arts

The harp, however, is working in the context of the wider music scene, and in the second part of the essay I would like to focus on three significant developments that are potentially just ahead of us.

I mentioned early on that some unexpected things can happen in the arts, and certainly one of the most surprising developments is the introduction of the Basic Income for Arts (BIA) pilot. This single initiative has the potential to have a transformative effect on music in Ireland.

The BIA is a pilot scheme that was introduced by Minister for Tourism, Culture, Arts, Gaeltacht, Sport and Media, Catherine Martin, of the Green Party, when the pandemic struck. The Greens had already negotiated a Universal Basic Income pilot into the programme for government in June 2020, and it was part of their election policies in 2019 before government, but the arts were not in their initial idea. It was when the pandemic struck that Minister Martin clearly saw an opportunity to pilot the idea in the arts scene and help artists at the same time. Since August 2022, therefore, two thousand artists and arts workers – 29% of whom are musicians – have been receiving €325 per week. The pilot, which lasts three years, is also being accompanied by a significant research project that includes a control group of one thousand people in the arts scene who are not receiving the payment, in order to draw a comparison.

In the Journal of Music, we have been following this research very carefully because it is extremely important to artists. The BIA could solve a lot of problems for them.

After six months, the results of the research were striking: 10% of the artists receiving the BIA payment showed a decrease in depression and anxiety. After a year, artists had improved life satisfaction, spent more time on their work, produced more work, and spent 40% of the payment on their artistic work.

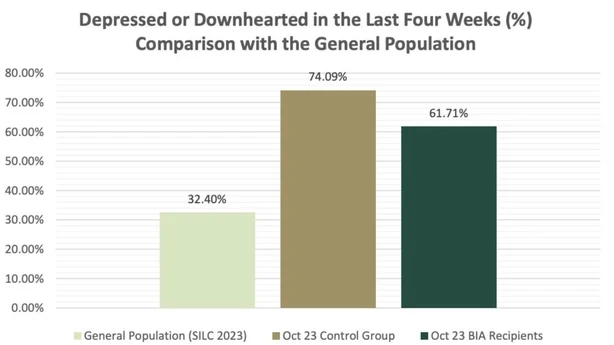

There is another part of the research, however, that is disturbing. After one year, those in the control group who reported feeling depressed or downhearted in the previous four weeks had remained stable at 74%, which may not be a surprise. Among BIA recipients, that figure had fallen to 62%, which is positive. However, the report also showed that these values are still ‘extremely high’ and that the average for the general population is only 32%. I work in the arts and know many musicians, and that figure still takes me aback. It shows just how important the BIA is.

The general noise from the government parties regarding the pilot has been positive so far, and when I talk to artists who are not in the pilot, they are hoping and betting on it being expanded next year. Indeed, there is an assumption that it will be continued because the government allocated €35m towards the scheme in the recent budget.

But things may not be as straightforward as we think.

We have to remember that there have been trials for a Basic Income in other countries, such as Finland, Canada and the United States, and in each case it was cancelled, or morphed into something else. It was changed because of a new government, an economic downturn, or results from the research that didn’t meet expectations.

If the Green Party and Minister Catherine Martin do not get into government again, what will that mean for the BIA? I am not sure who is going to champion this scheme or take ownership of it in the same way, despite other party promises. What will end up in the programme for government after the election? That is a serious concern and the first major challenge for music and the arts in Ireland. The BIA could be transformative, but the music community has to be prepared to fight for it over the next year.

A plan for the Irish music industry

The second challenge that I want to discuss is actually almost the converse of a BIA. It relates to the financial health of the Irish music industry overall.

The BIA pilot is an emergency measure. It is a social security net to protect those on low incomes, but amongst all of the attention for the BIA, the question has to be asked: where is our plan to raise artist incomes so that they are not reliant on schemes like this? Where is our larger ambition for this famous Irish music industry that we keep talking about?

Four years ago in the Journal of Music, we published an essay by a Paris-based Irish writer named Gareth Murphy. It was called ‘How to Transform Ireland’s Music Business’.

Murphy is from Dublin, his father was a former manager of the Bothy Band, he has worked in the music industry in Paris, and he is the author of Cowboys and Indies: The Epic History of the Record Industry – a survey of the entire last century. For his music business articles in the UK press he won Writer of the Year at the PPA Independent Publisher Awards, and for his liner notes for the vinyl re-release of the classic 1976 Andy Irvine and Paul Brady album, he was nominated for a Grammy. In other words, his insights into the international music industry are worth heeding.

In his 2021 essay, Murphy’s diagnosis of the Irish music industry was quite simple. Globally, he wrote, the music industry is broken into two components: the live music industry (concerts and festivals), and the recording industry (major labels and independent labels). The balance in size between the live industry and the recording industry varies from country to country, but almost nowhere, he said, is more lopsided than Ireland – we have a live industry, but our independent record label industry is extremely small.

Murphy makes a very significant point: he writes that because we don’t have a strong native record industry, ‘all the world-conquering music we think is Irish, is actually foreign-owned copyright being sold back to Ireland from the UK and America.’

He calls this ‘copyright drain’. It means that profits from those Irish music copyright licences are re-invested into the music scenes in those countries, and not necessarily into the next generation in Ireland. That’s why a strong indigenous industry of indie record labels is so essential. Think back to the 1970s when we had Claddagh, Gael Linn and Mulligan investing in our traditional music scene. We are still benefiting from that investment, and it is great to see Claddagh re-emerge again.

When Murphy’s article was published in 2021, it resonated with people in the Irish music scene. Steve Wall of the band The Stunning posted: ‘If you’re interested in how the Irish music business could be better read this. It’s a great read and echoes my thoughts entirely.’

Murphy’s solution is also quite simple: as we do with so many areas of our cultural life, we need to help our indie record labels grow. He describes labels as ‘beehives’. They are hives of activity that involve all sides of the industry from artists to producers to video makers to tour organisers. ‘Music is inherently organisational,’ he writes. ‘Nobody can do it alone. Labels are the heart pumps of the whole commercial ecosystem.’ For the musician, he says, everything begins with the record.

But what are we doing at the moment? Instead of investing in labels, we are providing literally millions of euro to individual artists to release albums on their own and to do all of the leg work. And almost every one of them has to become their own record label and learn all of the skills involved in running such a company every single time, and then that new label just fades away from lack of investment. Without growing our record industry, it means that many artists spend their lives living off grants.

Murphy published this essay in March 2021. In December 2023, the Arts Council published its new music policy and said that it would commission research into supporting the commercial music industry, which I hope means indie labels. To date, almost a year later, no such research has been commissioned. If it is commissioned next year, then we will hopefully see a significant increase in the investment in small independent record labels. That could be transformative because it could start to grow our music industry and give Irish musicians more support. Like the BIA, I believe it is the second development that the music community should be highlighting and striving for.

Decentralised funding

The third issue I want to highlight relates to support for music and the arts throughout the whole of Ireland, and I want to begin by mentioning the Achill International Harp Festival.

This festival, like Harp Ireland, began in 2016 and it very quickly established itself as an innovative international festival for harping. It was founded by the wonderful harper Laoise Kelly and it had a superb voluntary committee. Based on the Mayo island of Achill, which is almost shaped like a harp, there was a creative magic to the festival.

Now, however, the festival is gone. The pandemic was difficult enough, but ultimately it was the workload on a voluntary committee that made it impossible to sustain. It closed in 2021 after 5 years.

This month, I heard that another great harp festival is not taking place next year. For the first time in 23 years, Scoil na gCláirseach in Kilkenny, the only festival of the early Irish harp in the world, founded by Siobhán Armstrong who featured in the aforementioned Creedon’s Musical Atlas of Ireland, will not take place next year. Again, this is about fluctuations in funding and the difficulties faced by a small committee working for very little for a long time. It is just not sustainable.

I also recently heard that the Galway Early Music Festival, which for 28 years often featured the Irish harp, was refused funding, and there are other examples of festivals disappearing.

There are lots of reasons why events and organisations end. Nothing lasts forever, but we have to look closely at what is happening.

If you add up the increase the Arts Council has received over the past four years, taking the initial 2020 figure of €80m as the baseline, the additional funding amounts to €204m. That is a significant figure.

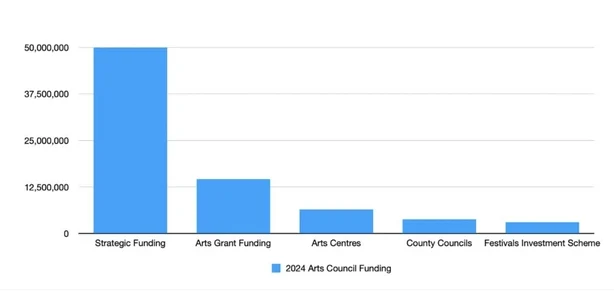

But where is it going? If you look at the Arts Council’s Strategic Funding scheme, which is the largest pot of funding that the Arts Council has, by some margin – €50m, or 37% of its entire 2024 budget – 70% of that funding is going to organisations in Dublin.

It is not just the amount, it is the type of funding. After Strategic Funding, the next largest tranche of Council funding is the €14.6m spent on the Arts Grant scheme, which is for smaller organisations, followed by the €6.5m spent on arts centres, €3.8m for local councils, and €3m for the Festivals Investment Scheme for small festivals.

The average grant in Strategic Funding in 2024 was €465k; for organisations in the Arts Grant category it is €80k. The reality is that if you want access to significant and sustainable funding as an arts organisation, you have to try and get into Strategic Funding. It could be the difference between 4 to 8 staff and 1 to 2 staff.

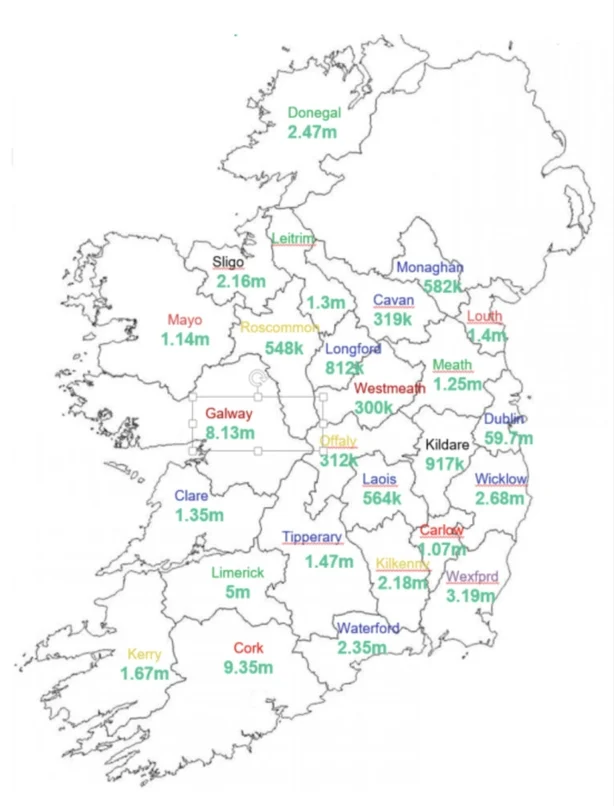

Even when organisations from outside Dublin make it into Strategic Funding, their combined allocation is dwarfed by organisations in the capital. In 2024, Galway and Limerick both received just 6% of Strategic Funding compared to Dublin’s 70%, Cork received 5% and Kilkenny received 3%. Eight counties didn’t receive any Strategic Funding at all: Cavan, Kildare, Laois, Mayo, Offaly, Roscommon, Tipperary and Wicklow.

If the majority of the new funding is going to organisations in Dublin, which, because it is so expensive, is probably swallowing up a lot of the increase, with a limited return, then it makes it impossible to build a broad arts infrastructure around the country.

It is true that some organisations in the capital have a national remit, but what does that mean in practice? It does not create a sustainable arts infrastructure in 25 other counties, plus the north, and by that I mean organisations that have staff, can grow, and create more opportunities for artists. Dublin has just 29% of the population.

I highlighted this disparity in an article in October titled ‘Why We Need to Decentralise the Arts Council’. In response, the Communications Director of the Arts Council contacted me and said the article was ‘disingenuous’ by focusing on Strategic Funding, and pointed out the investment the Arts Council is making in the rest of the country. It is true that the Council provides many individual and organisational grants throughout Ireland, but I hope it is clear why I did take that focus. The difference between Strategic Funding and every other grant scheme is considerable. It allows an organisation to employ staff and build for the future. Everything else is precarious.

As a counter argument, the Arts Council sent me the overall grant figure for funding around the country, but I don’t think that it does change the situation. It shows Dublin receiving €59.7m of all funding (which amounts to 53% of the total figure in this map), and each county is still far below the capital.

If you want to build your arts infrastructure, you have got to be in Strategic Funding. Thankfully Harp Ireland is, although its funding is not near the average.

In my recent article, I called for the Arts Council to set up offices in Cork, Galway and on the border, and distribute their funding accordingly. Until they do, we will continue to see green shoots appearing around the country and then disappearing again.

This centralisation of arts funding is, I believe, the third significant challenge that faces Irish music into the future.

Challenges for the future

We have a remarkable music scene in Ireland, with a rich history, but there are many competing voices out there. The political party manifestos for the forthcoming election contain many ideas for the arts, and the Arts Council has a range of plans too. Meanwhile, low incomes, music spaces, unaffordable housing and high rents are to the fore of musicians’ minds, but without the expansion of the BIA and addressing the lopsidedness of our music scene by growing our record industry, these issues will rumble on. Meanwhile, the centralised funding undermines our entire wider scene. For the benefit of the future of music in Ireland, the music community needs to focus on these challenges.

Toner Quinn is Editor of the Journal of Music. His new book, What Ireland Can Teach the World About Music, is available here.

This is an edited version of the Harp Ireland/Cruit Éireann Annual Lecture, given by Toner Quinn on 17 November 2024 at the Royal Irish Academy of Music. Find out more about Harp Ireland here.