Dec 24, 2024

Dec 01,2024

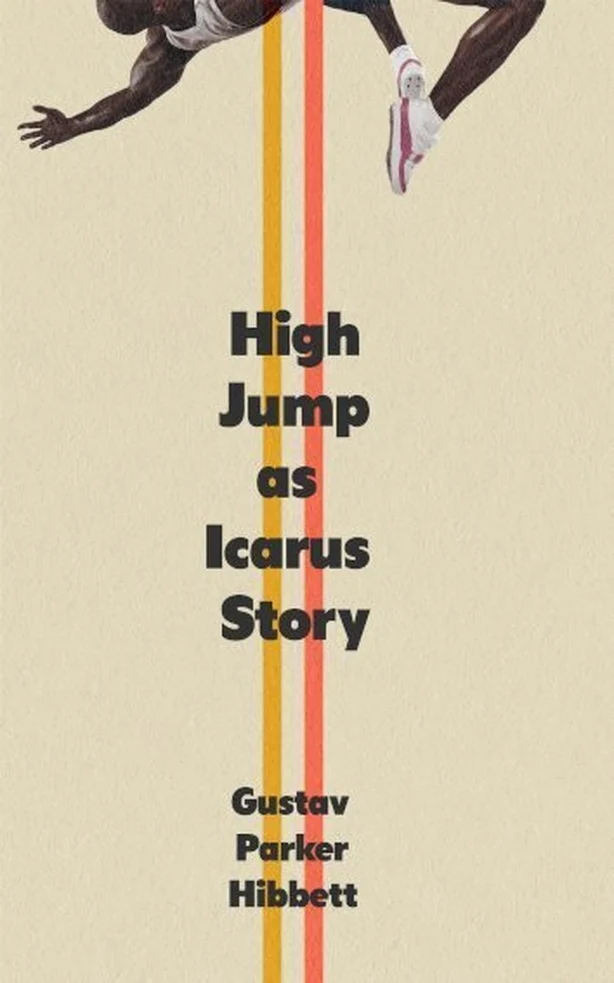

In July this year, Gustav Parker Hibbett published their extraordinary debut poetry collection High Jump as Icarus Story with Banshee Press.

Already highly-anticipated, given Hibbett’s status as an award winning writer with much to say on the similarities and differences between Ireland and the poet’s native US, when the collection came out it was warmly received and seemed to promise good things from both Hibbett and Banshee.

An extended metaphor on the moment of transcendence that both the sport and poetry produce, High Jump takes the reader on a journey from New Mexico to West Cork, through mythology, pop culture, considerations of blackness and queerness, and tender deconstructions of modern masculinity.

But now with the book having received a nomination for the prestigious TS Eliot Prize, for the third time in just two years an Irish publishing house has been in contention for one of the biggest literary prizes in the world. And given that this is not only Hibbett’s debut, but the first time that anyone on Banshee’s poetry list has been nominated, it is quite the feat indeed.

We thought it would be prudent to speak to both the poet themselves and the editor who published their book - Jessica Traynor is a remarkably storied poet in her own right, who was appointed as Poetry Editor for Banshee Press in 2023.

Gustav, what has the experience of being nominated for the TS Eliot Prize been like for you?

I’d say 'whirlwind’ is a good word for it. So much has shifted for me, but in the loveliest way. I’ve been over to London to record some poems and make a video explaining the thought process behind High Jump as Icarus Story. And I was kind of terrified too, because it suddenly felt like this huge thing.

In terms of trying to sell the collection to the States and get a publisher there, it’s also been a huge boost; particularly since that’s my home market. Interfacing with agents and publishers, there’s this question of what I want to do next for my career… which is both strange and elating because, as I was saying to my partner the other day, I didn’t even know I was gonna have a career until about a month ago!

Up until the publication of the book and the nomination, I thought I might need to continue fighting for a lot of years. Now I feel like I have some sort of career security, or at least what passes for security in this field. It’s bizarre.

What do you think the future looks like for you? Do you see yourself continuing to write poetry? Might you branch out into other areas of literature?

I’m a few months into the final year of my PhD and my dissertation is actually in the area of creative nonfiction. To be honest, I’ve sometimes found that difficult because I’m not sure that nonfiction is necessarily my medium, though I am interested in continuing honing my craft.

There’s also that question of whether I want to pursue a teaching career within academia. I’ve done a lot of research and reading for my PhD and have so many ideas about how I might pass on what I’ve learned to a different generation of scholars. Through teaching Black Lit classes, for example, or Black Theory. To be in an English department where I could bring my skills to bear and open up new ways of thinking that unite all these creative and critical lines.

Non-fiction and poetry have tended historically to lend themselves well to each other. Do you find that the techniques you're using in your nonfiction writing and your poetry feed into each other?

I'm still hoping for that full circle moment, though I do think that writing in a different medium has renewed my sense of poetic possibility.

Jessica, how has it been working with Gustav for Banshee? How did your editorial relationship begin?

It’s been a gorgeous process. I came into Banshee after we’d already published Bibi Ashley's first collection (Gold Light Shining, 2020) as well as Rosamond Taylor's first collection (In Her Jaws, 2022). Dylan Brennan's first collection (Let the Dead, 2023) had already been taken on, and although his was the first book I’d done some work on from beginning to end, Gustav was the first poet I was able to approach myself.

I’d published some of Gustav’s poems in the magazine and was really excited by their voice. I thought there was something so unique about the tone; a real lightness of touch and wit, and a kind of a poignancy that was beautifully captured on the page. I think that’s a rare thing to come across; this sense of execution matching ambition, you know? The juxtapositions that Gustav creates in their work are so apt and true and I was very keen after the magazine publication to see more. We’d met at a couple of launches, and I think I reached out not long after first meeting.

Every first poetry collection is a kind of leap into the unknown, but we're really happy that it’s paying off for everyone.

We discussed different options for publication. I expressed an interest in seeing a manuscript and and when it eventually came in, it was a no-brainer for everyone at Banshee; (Co-founders) Emer (Ryan) and Laura (Cassidy) included. We collectively just thought ‘this is so beautifully formed’ and Gustav was savvy enough to come to us with insight and questions already prepared. We worked together over a number of drafts. And I suppose one of the nice things about Banshee, being an independent publisher, is that you have the time and luxury of focusing your attention on a single manuscript. Obviously there are deadlines, but we didn’t feel rushed in the process.

We were also able to kind of leverage some of our contacts for outside perspectives, because Laura, Emer and myself were very aware all the time that we were coming to this piece of work as three cis white ladies… That made the editorial input from all sides feel very well-rounded. We’re aware too of how lucky we are to have had Gustav trust us with their work, since we’re a relatively new publisher, based in Ireland, and Gustav had already published lots in the US.

Every first poetry collection is a kind of leap into the unknown, but we’re really happy that it’s paying off for everyone. The work has been deservedly very well received and it’s hugely exciting for us to have a poet at the Eliots…

Gustav, when you sent the manuscript to Banshee, was it something that was already nearly fully-formed or were you still trying to bring aspects of it together?

It was fully formed in terms of the ideas, but I'd say that the editorial process tightened up the manuscript in really crucial ways. This was my first foray into publishing a whole collection, and throughout I felt welcome and secure enough in my relationship with Jess to open the material up think about deepening some of the themes. I even ended up writing some new poems, which were eventually included in the book, and it felt good to have that kind of external validation when it came to just knowing what I was doing. Writers sometimes get that sense that what their doing won’t be understood, so having a dialogue was a really useful thing.

Watch: Gustav Parker Hibbett talks about their work

A huge part of the working relationship was about seeing where I was going and teasing out whether taking one direction or another would actually make sense for a wider readership. High Jump started out as something maybe a little experimental, and I was probably a bit tentative before Banshee took it on.

The central motif of the high jump allows for the deconstruction of masculinity through the literary lens of sport. Take John Updike’s Rabbit series, for example, where the main character has history as a basketball player, or Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead who plays American football… What was it about the high jump—beyond the literal connection to Icarus reaching for the sky—that attracted you towards it as a suitable motif?

It came very naturally to me as just a very important aspect of a certain part of my life. The high jump created a space for me where I finally felt able to trust my body, my instincts, myself, and the end result was always something beautiful, you know? I was interested in beauty on its own artistic merit, but with the high jump it’s always coupled with this very definite sense of finality; that fall on the mat at the end of it which comes just after this mini moment of transcendence where you’ve ascended through sheer will and contortion. That kept me buoyed for so many years.

So when I came to poetry, I began to have a similar relationship with the art in that my knowledge of its completion felt almost somatic. Reaching for that moment of transcendence as a way of expressing the very real things that happen in your life.

(Jessica Traynor speaking) There’s also that inevitable idea of failure at the end, which Gustav and I both came to after discussing Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry. The way he talks about every poem being doomed to failure because it tries so hard to almost break the limits of its own form. About language, and perhaps art in general, trying to transcend itself into action. The mirroring that can be found in high jump astonished me when I first read Gustav’s work.

Gustav, you mentioned beauty as an important motif as well, and I’m wondering how the collection squares itself with the particularly fraught political moment we’re living through—for the United States in particular, but also in Ireland… Queerness and blackness are both explored in High Jump, and are rendered just as strongly as those other themes of masculinity and beauty. Do you think that beauty and the underlying righteous anger of some of these poems has a role to play in rebuking the far right worldview?

I’m probably borrowing a lot from thinkers like Sylvia Hartman or Christina Sharpe, who’ve talked about the power of beauty; somethins which Christina Sharpe calls beauty as method, or methodology. Appreciating beauty and living beautifully can be utilised as a radical tool of resistance, limited in certain ways, but in shaping the aesthetics of the world we want to live in, of what we can control etc. Beauty can be an exercise, therefore, in exterting control over what we can control.

There’s this moment in the Pelé documentary where Brazil are in the final of the World Cup. They’re playing against this team that’s feted to win, everyone in the stadium is initially supporting Brazil’s opponents, but as they watch Pele play, suddenly they start cheering for him and willing him on. Despite the racism, despite everything, despite all of these kind of things that act as barriers, in other words, the beauty Pele displays in that moment manages to cut through it.

Jessica, how did you feel editing this collection as someone who has been through the editorial process herself?

One of the things that we’re guided by at Banshee is whether we’ve seen this sort of work being done before, or whether there are other, perhaps better-suited outlets for that work. Is there something we can offer, in other words, that’s a bit different? Irish poetry has diversified a lot over the course of my own career and may actually be ahead of fiction in terms of the sheer number of Irish poets from different backgrounds. We’re making good progress after a very long time of there being none.

So when it came to editing Gustav’s book, it was really just about amplifying their experience and making sure that I was able to offer as well rounded an editorial service as possible. I just felt really excited about the work, and am proud to have discovered something I hadn’t yet seen.

The winner of the TS Elliott Prize will be announced on 13 January 2025. High Jump as Icarus Story is published by Banshee Press.