Dec 24, 2024

Nov 23,2024

The recent renaming of Trinity's George Berkeley Library in honour of the late, great poet Eavan Boland is undoubtedly a good thing, but if we want to rewrite the Irish literary canon to be more inclusive of women, we have much more work to do.

One of the joys about working with books is the rediscovery of authors who, for one reason or another, have gone out of fashion. This can be for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a writer’s relevance balloons because contemporary events resemble something from an earlier time. Sometimes tastemakers discover an author quite by accident and their sudden championing encourages others to follow in their wake.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

Listen: Sunday With Miriam on The Eavan Boland Library

Sometimes, though, important authors or artists are neglected because of the political and social mores of their time, and their rediscovery later can only be attributed to wholesale changes in outdated power structures. Ireland is filled with such examples, especially when it comes to women.

Whether conscious of it or not, we stand in the long shadows of these women, and it's high time they got the recognition they so richly deserved while they were still living.

That women have been marginalised in Irish society will come as no surprise—having dealt with everything since the foundation of the State from misogyny in the workplace to lack of access to contraception to having to struggle for bodily autonomy—but in a country that celebrates its writers to such an extent that there are statues, libraries and streets named after male authors, we are only now coming to terms with the fact that female authors have not received the same treatment.

Even celebrated writers like the late Edna O’Brien and Eavan Boland—whose name recently replaced philosopher and slave-owner George Berkeley at Trinity College’s main library—had to struggle for years before finally being given their dues. The censorship and banning of Edna O’Brien’s work in the early part of her career is well documented; O’Brien and Boland ultimately had to leave Ireland to allow them both to copperfasten their rightful positions within the literary canon, and yet even then, for every example of a female author who is embraced for their genius—even if only posthumously—there are a dozen others who have yet to receive the plaudits they deserve.

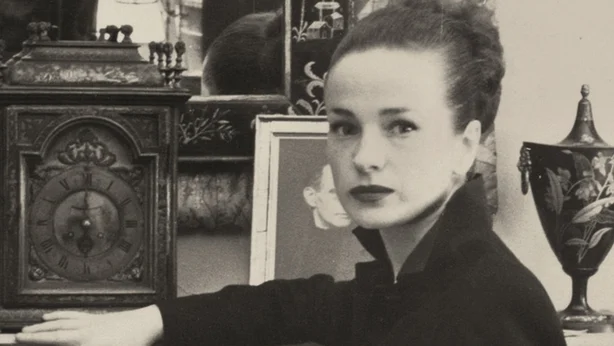

Take Maeve Brennan, the glamorous, lyrical protégé of New Yorker fiction editor William Maxwell, who died sometime during the 1980s forgotten and in almost complete destitution at her home in Queens after struggling for years with mental health issues and addiction. Or Ethel Voynich, the revolutionary daughter of landed Cork intellectual and mathematician George Boole, who abandoned her life of privilege in order to produce one of the best-selling novels in the history of the Soviet Union, The Gadfly. Or lifelong Republican and anti-fascist agitator Dorothy Macardle, whose participation in the Irish Revolutionary War during the 1920s belied a brilliant and often overlooked body of weird fiction, criticism, agitprop and poetry.

Whether conscious of it or not, we stand in the long shadows of these women, and it’s high time they got the recognition they so richly deserved while they were still living. And given that the recent global success of Irish writing has primarily been driven by contemporary female authors such as Anna Burns, Lucy Caldwell, Emma Dabiri and Sally Rooney, let us not regress again into that pattern of selective remembering that has dogged us for centuries. If you must read Irish, read Irish women. All of us will be so much the richer for it.