Dec 24, 2024

Nov 19,2024

Timothy O’Neill is an expert calligrapher whose work can be found in collections worldwide. Some of his projects include commissions presented to world leaders - Presidents Clinton and Obama, Pope John Paul II and Japanese Emperor Akihito.

His latest book, The Irish Art of Calligraphy: A Step-by-Step Guide, sees Tim draw on his experience to explain the basics of traditional Irish calligraphy and design, and also offer a glimpse into the beginnings of Ireland’s weary links with medieval Europe.

In this exclusive excerpt, Timothy gives us an overview of what Ireland was like in the ninth century, and the origins of writing, as well as some practical tips on getting started with your own calligraphy practice...

Ninth Century Ireland

In the ninth century, Ireland did not have any towns. Instead, across the countryside and throughout the midlands in particular, there were many monasteries. Unlike the medieval monasteries of continental Europe, which had large, communal stone buildings where monks lived a common life, Irish monasteries often consisted of several small churches and a collection of individual cells, or huts, within a circular enclosure. In the countryside, extended

families lived in similar structures surrounded by earthen banks, topped with wooden fences, or on artificial islands in lakes called crannogs. Security was a serious issue as warfare was frequent and cattle-raiding common.

By the year 800, Ireland had become a predominantly Christian country, a religion whose beliefs and traditions were preserved in books written in Latin. Religious teaching always stressed the message of the written word, and images of Christ and the saints frequently showed them holding a book as a symbol of authority.

First steps in writing

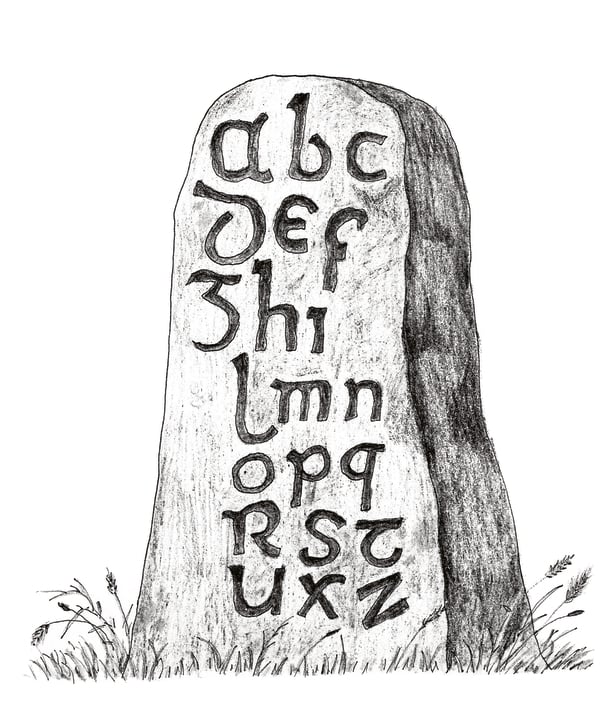

A stone with the letters of the alphabet carved into it survives in the church of Kilmalkedar in County Kerry. Teachers may have encouraged young students to trace the shapes with their fingers. Roman sources tell of students spending their days tracing with a pointed metal stylus small letters carved on wooden blocks. In this way, they learned how to train their fingers to hold the stylus and trace the shapes. When they were deemed ready, the students were introduced to wax writing tablets. These were flat pieces of wood, hollowed out and filled with beeswax that was coloured black. They could be held comfortably in the hand. A pointed metal stylus was used to write into the wax, and the surface could be erased by rubbing over the letters with the top of the stylus, which was smooth and rounded.

Everyone used these wax tablets for making notes and writing letters before the year 1000 and before paper became available in Europe. Among the oldest samples of Irish writing are psalm verses incised on a set of six wax tablets. These were discovered in a bog near Ballymena, County Antrim. They are now displayed in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin.

Quills

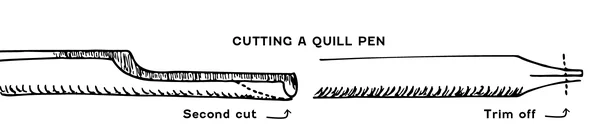

Whenever new books were needed, they were written with quill pens. The best quill pens were, and still are, those made from the wing feathers of swans or geese. The newly plucked quills must be kept for a time in a warm, dry place until the barrel, or tubular section, becomes transparent. Then, after the thin waterproof outer coating has been scraped off and a slit inserted to help the ink-flow, the nib is cut to size, usually in two steps, using a sharp, single-edged knife (the original penknife). Finally, any of the remaining soft vanes or 'flights’ of the feather are plucked off to give the pen better balance.

A faster process to prepare quills may also be used. This involves removing their tips and soaking the feathers in water for about a day, until they become soft. Then, having taken them out and shaken off any water, they should be plunged into very hot sand for a few seconds, with more of the hot sand being spooned into the barrels. The quills harden immediately and become clear and ready for shaping. (Beware: the hot sand is dangerous and can cause serious burns.)

A quill pen may be difficult to prepare and cut, but when ready, it is the perfect writing instrument. This is because it is almost weightless and has a natural curve to fit the hand; its tip can be cut to any width or shaped to a point. Moreover, it is made from material like human fingernails, so that writing with a quill is like writing with one’s fingernail.

Getting started

When writing a script, you quickly learn that it is the pen, not the writer, that does the work. When learning to write one of the traditional medieval scripts then, it is necessary to use a pen with a broad, flat nib that is between one and two millimetres wide. There are many brands of such pens available, often sold in calligraphy sets. The ink for these pens comes in a cartridge and flows freely.

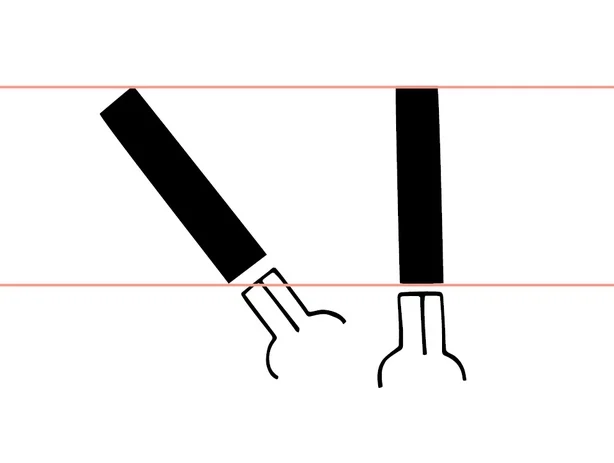

With such a pen it is easy to understand how letters are formed. So, to begin with, it is important that you get to know the pen, that the ink flows freely, and that you can make good, sharp black marks on the paper. Very soon you will notice that, depending on how the pen is held, the same nib can produce lines of different thicknesses.

The most important thing about writing a script with an edged or square-cut nib is that the angle at which the pen is held remains constant. ‘Pen angle’ means the angle at which the nib is held to the ruled writing lines.

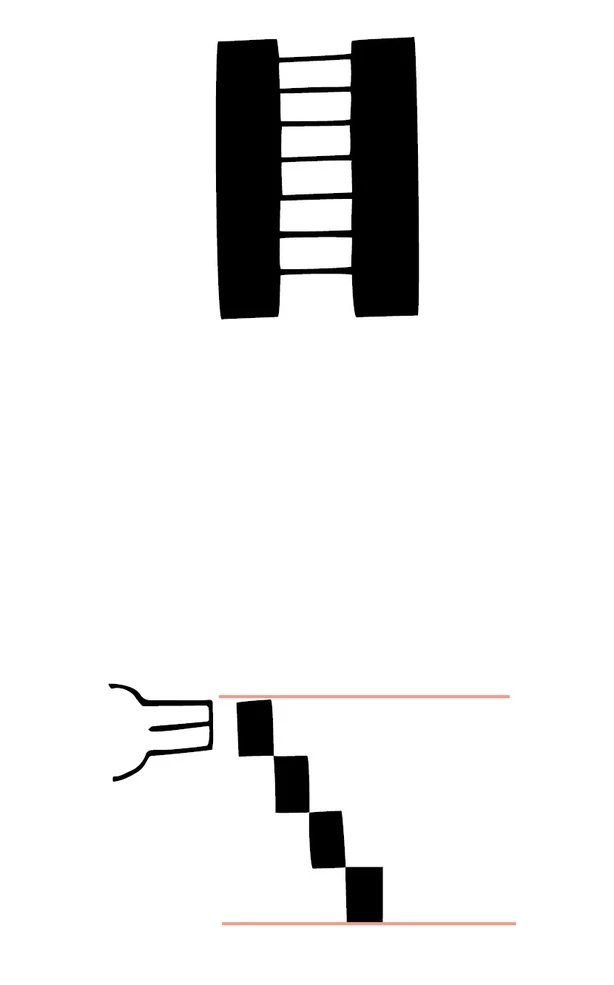

It is not difficult to learn the basics of how to write in a style like that of the gospel books of Durrow, Lindisfarne, Kells or the Irish Gospels of St Gall (Cod. Sang. 51). The first thing to remember when beginning to write in this style is to hold the pen with the nib parallel to the writing lines. This is not difficult to check, because when the pen is held at this flat angle, the upright strokes are the full thickness of the nib while the horizontal strokes are the thinnest possible.

A practice exercise would be to make ‘ladders’ like the one above while taking care not to turn the pen between the fingers. When learning a formal script, such as was used for copying books, you write between two lines to keep the letters at a uniform height.

This height is calculated to be about four or five times the thickness of the nib. Everything is determined by the nib-width, so when the size of the nib is selected, the letter height is calculated and the writing lines are ruled.

When learning a formal script, such as was used for copying books, you write between two lines to keep the letters at a uniform height. This height is calculated to be about four or five times the thickness of the nib. Everything is determined by the nib-width, so when the size of the nib is selected, the letter height is calculated and the writing lines are ruled.

The Irish art of calligraphy: a step-by-step guide is published by the Royal Irish Academy - find out more here.