Dec 24, 2024

Oct 23,2024

County Donegal has long been home to a rich tradition of painters, and Ann Quinn stands out as one of its most remarkable.

Northern Light, now on view at the Regional Cultural Centre in Letterkenny, celebrates her distinguished career with a mid-career survey that spans over 15 years of her practice. Raised on a dairy farm in East Donegal, Quinn's atmospheric paintings are deeply rooted in the local landscape, capturing the subtle magic of fleeting moments such as dusk or the arrival of winter. Her work combines careful observation of light and nature with reflections on memory and the human presence in these spaces.

Curated by Daniel Nelis, Northern Light offers an immersive journey into Quinn’s exploration of place, time and people.

The Regional Cultural Centre invited writer Aidan Dunne and filmmaker Charlie Joe Doherty to spend time with Ann and delve deeper into the themes and significance of Quinn’s work.

In her paintings, Ann Quinn invites us into a familiar, easily recognisable world. Just as with our everyday world, though, there is always more going on than surface appearances might suggest.

The majority of the paintings in this exhibition draw on locations within a two-mile radius of her home, itself close to the family farm where she grew up. The valley referred to in the tile of her painting The Valley when the Mist is Strong is her own valley, and records a phenomenon that still compels her interest: a thick, low-lying mist that creeps over the land at certain times so that it is like, far from the sea, an inland sea, a waking dream of the ocean. The transformative magic of this vision clearly casts a spell over her and indeed, she has commented in the past that she paints to capture "certain rare moments in life when I feel I am witnessing magic."

She may not say it, but painting itself is magical for her. Each of her works is conjured up, like that vision of the sea, a manifestation at once gossamer thin, often manifest through an intricate patterning like craquelure, fleeting yet at the same time physically irrefutable. While she is a representational painter, which is what allows us as viewers ready access to her world, she is not a realist painter in the sense that her paintings are not neutral, documentary accounts of what is there to be seen at a particular time and place, they are not photographic snapshots. While she does take many photographs, and uses them as points of reference, much in the way that artists would have used sketched studies prior to the invention of photography, her paintings are never simply copies or reproductions of photographs. Each painting is not only a subjective view, but an interpretation, a substantially reordered construction that incorporates elements drawn from memory, elements of the photographic images referred to and other factual, visual information. Her technique can also encompass pools of pigment floated on the surface, like clouds, and occasional runs of thick impasto, so that passages of any particular painting can seem to teeter on the edge of abstraction, as though the whole thing might at any moment dissolve before our eyes, like an hallucination.

All of these pictorial components are combined in compositions that generate hints of potential narrative interpretations. Narrative hints rather than narratives per se because the paintings are not neat, conclusive stories with a beginning, middle and end. Rather they open up areas of speculative interpretation that may find echoes in our own experiences - and might even surprise the artist. In doing this, they hold out the promise of enriching our understanding of life and being, and of the artwork.

Quinn has made portraits, and is an extremely fine portrait painter as is evident from the works included, including her self-portrait (made at the invitation of the National Self-Portrait Collection in UCL) but has never felt personally drawn to portraiture. Legnathraw and Meenagrauv, both outstanding landscapes, are in effect portraits of houses, indicative of time passed, lives lived. They were inspired by a commission from the Donegal Museum as part of the Decade of Centenaries programme. Of two allegorical works produced during covid lockdown, The Discovery highlights a woman on the threshold of a huge, unmistakably American barn, and The Artist finds a woman searching a forest by torchlight. The cinematic character of both corresponds with onscreen sources.

The youngest of a large family, as a child on the farm Quinn liked to wander alone and allow her imagination free rein as she explored the boundaries of the land. The shadowy edge spaces became for her a realm of fairies and other fantastic creatures, an enchanted world beyond habitual visibility. She has clearly retained her appetite for the fantastic in the ordinary. Her 2020 painting At the Approaching Presence of Night taps directly into local lore concerning Binnion Hill in stories relayed to her by her father, involving a fleeing hare. In the stories, the hare, a creature steeped in mythological associations, mysteriously transforms into an elderly woman with an injured ankle as it approaches an old graveyard.

Overall, a sense emerges, in her paintings, of a farm as a kind of kingdom.

By that point, Quinn was long back in Donegal, having spent about twenty years based in Dublin, where she initially went to study art at NCAD. When she arrived in Dublin she was, she notes, very much a country person in the city, and it took her quite a while to become acclimatised to the urban environment, which she explored little by little and, in time, became and remains enormously attached to. If different from the country, the city had its own poetry for her. That poetry is beautifully articulated in her composition Twilight on Harrington Street, recalling where she lived for many years. In this painting, much of the clutter and rush of the city evaporates as the unexpected calm and quiet of the evening takes over.

If Dublin contributed to shaping her vision, it also provided her with a change of perspective on her home, a new standpoint. My Parents, Seen Through the Parlour Window, in which the artist's mother keeps vigil with her ailing husband, casts the painter as an outsider, an observer, even as the reflected tree suggests genealogy and rootedness. And years spent largely away clearly did not lead her to developing a romanticised view of the rural life she’d known. If anything, the opposite is the case. She returned with sharpened vision.

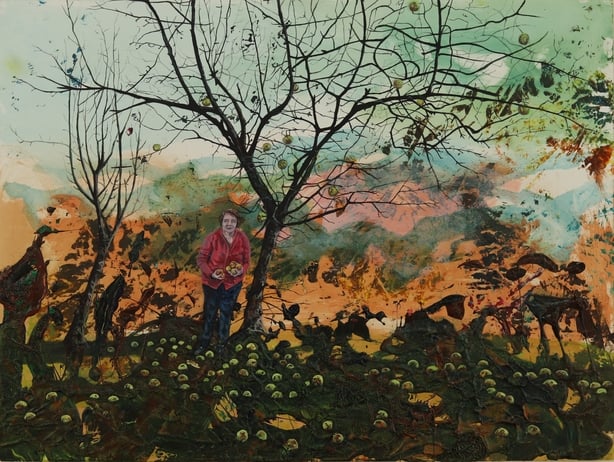

Overall, a sense emerges, in her paintings, of a farm as a kind of kingdom. If that implies grandeur, well, there is certainly grandeur in, for example, the beauty of nature, which is generously evident in many works. In several paintings the sky, flushed with evening light, charges the scene with tingling energy, as in Mother, where the smiling figure pauses in gathering windfalls, or Suspended at Dusk, in which the glare of a car’s lights, as it negotiates a tree-fringed road, is dwarfed by the lush extravagance of the setting sun spreading swathes of colour across the heavens. It’s important to point out, though, that Quinn does not have an idealised view of the natural world, perhaps partly because she is so firmly rooted in the practical realities of the countryside. She is alert to the numerous tensions between farming and nature. The strained if ultimately soothing harmony of the vista in John Craig’s Farm unmistakably suggests a brimming, unruly nature just about held in check, a feeling that recurs in many paintings.

A certain starkness, including a spike angularity in the vegetation, is characteristic. The artist has written of being most inspired by the winter months: "I prefer the raw mood and light of a season when the elements of nature are stripped to their bare essentials." Stays in Norway, one commemorated in North is Calling, confirmed her feeling that she is somehow suited temperamentally to northern latitudes. And, as her work confirms, she is drawn to the edge of the day, as the light ebbs away.

In the kingdom of the farm, there’s evidence of the farmer’s dominion in, for example, the orderly line of cows filing back to their field after milking, in My Father’s Cows Making their Way Down to the Burn Fields After Milking. Or in the farmer atop a veritable monument of silage, its black plastic covering held in place by a grid of tyres in Derek and His Dog on Top of the Silage Pit. The grid of tyres is dominant in My Ancestral Home, where it could symbolise the whole ambitious enterprise involved in maintaining the tenuous human grasp on the land, while the mist flows through the valley beyond, a river of time. Sovereignty over anything comes at a price. A farm is necessarily a tough, demanding domain, a sliver of hard-won order imposed on a chaotic world. Its continuance exacts a heavy toll, figuratively and on occasion literally, overwhelming and consuming its inhabitants. There’s a sense, in My Father’s Final Journey, of the farm reluctantly surrendering its servant.

As with any kingdom, the sense of power and control it offers can inspire expansionist dreams and dynastic ambitions, all of which provides potent dramatic fuel, from Yellowstone to Jean de Florette, all the way back to King Lear or, more locally, John B Keane’s The Field. Such dramas usually confirm that the lived reality is always contingent and transitory, even inherently tragic, in Ireland as elsewhere, as Keane’s play makes clear. Several of Quinn’s paintings broach these concerns about our fierce identification with the land. In The Byre, in a way a strikingly theatrical composition, the farmer sits in the doorway of a milking parlour, a weary, pensive figure, somewhat forbidding, a brooding Lear, perhaps. In the farmyard foreground, several animals, unlikely companions, lap at rivulets of milk spilled from an overturned churn. They are a dog, a cat and a kitten, a crow and a wagtail, while, perched on a gate, a cockerel watches. Other cats lounge, close to the farmer. A single swallow flies free in the one corner of sky glimpsed beyond the slightly oppressive yard.

It’s hard to resist the allegorical implications of the work’s singular assembly of detail. Animal Farm might come to mind given the menagerie, but not its politics, rather in the fable-like way the different animals might embody competing human perspectives. Spilled milk, soured milk. A dairy farm is built on the rigid armature of its milking schedule, and the weary farmer is the slave of that schedule, tied to time. These ideas are left for us to deal with, hard truths. Similarly, two dogs feature prominently in The Successor. At first glance, it appears the dog to the right, appearing purposeful, teeth apparently bared, might aim to take the place of the one on the left. Even given that Quinn’s conscious intention is that the overalled farmer in the painting is the successor in question, it is tempting to see the dogs as substituting for human actors - not least given the relative abstraction of the background, which heightens the feeling of allegory.

The artist acknowledges that her own attitude to animals has shifted significantly On the farm, the natural world was inevitably viewed unsentimentally. Animals were livestock, or they were useful about the place in other ways. Seamus Heaney wrote indelibly about being a child in such a world in his first major collection of poems, Death of a Naturalist. "I was six when I first saw kittens drown…" he recalls in The Early Purges, a poem that develops into a litany of animal mortality that gradually becomes numbly normal until:

"And now, when shrill pups are prodded to drown

I just shrug, 'Bloody pups’. It makes sense

…on well-run farms pests have to be kept down."

In Quinn’s case, such events as a chance encounter with a cow that had died (perhaps her painting, Floating on the Other Side, relates to this memory), proximity to the slaughter of a pig, and the unexplained disappearance of a dog whose attitude to sheep was in doubt became memorably engraved in her consciousness. But that remembered farm dog was not a pet. One could say of her recollections of such events that they were there, at the back of her mind, but she did not know how to process them. Any notions of animals as pets, or the idea of building up relationships with them, were never countenanced. But she did come, belatedly to such ideas, and to the ethical and moral implications of seeing animals as conscious, sentient beings, questions that, her work suggests, now greatly preoccupy her.

Consider the conceptual leap from the view of cows after milking in My Fathers Cows…, to Byre, which we can read in terms of anthropomorphic symbolism, to The Moonlit Existence of a Powerful Cow, or indeed The Beast of the Field. Broadly speaking, in the first case the animals are livestock, part of the farming process, in the second, they are allegorical stand-ins for humans, but the final paintings invite us to consider the cows in their own right, as conscious animals. We can look to two small paintings focusing on cats, My Beloved Cat and All Creation will be Renewed, as representative of transitional moments. The chance adoption of a cat which later perished enabled the artist's remaking of her relationship to animals, establishing the possibility of emotional attachment and a sensitivity to the creatures’ experiences.

Following on from Peter Singer’s call for a reassessment of our treatment of animals in his benchmark book Animal Liberation in 1975, there has been a seismic shift in our knowledge and appreciation of the inner lives of non-human species, and examination of the ethical questions posed. Quinn’s personal reassessment of the question is encapsulated in her recent, extraordinary painting A Moment in the Essence of Loneliness. In the work, the hapless, helpless animal, centre of the appraising looks of dozens of buyers at a cattle mart, gazes mutely out at us, the viewers. Each individual human at the mart is strongly characterised, and we get a sense of their varied thoughts and travails, their human problems and constraints, including their boredom and impatience with things. But the cow, the centre of their attention while comprehensively disregarded at the same time, is the painting’s consequential protagonist, and we are challenged by its gaze.

Northern Light is at Regional Cultural Centre, Letterkenny until the 30th November 2024 - find out more here.

All pictured artworks © Ann Quinn