Dec 24, 2024

Oct 23,2024

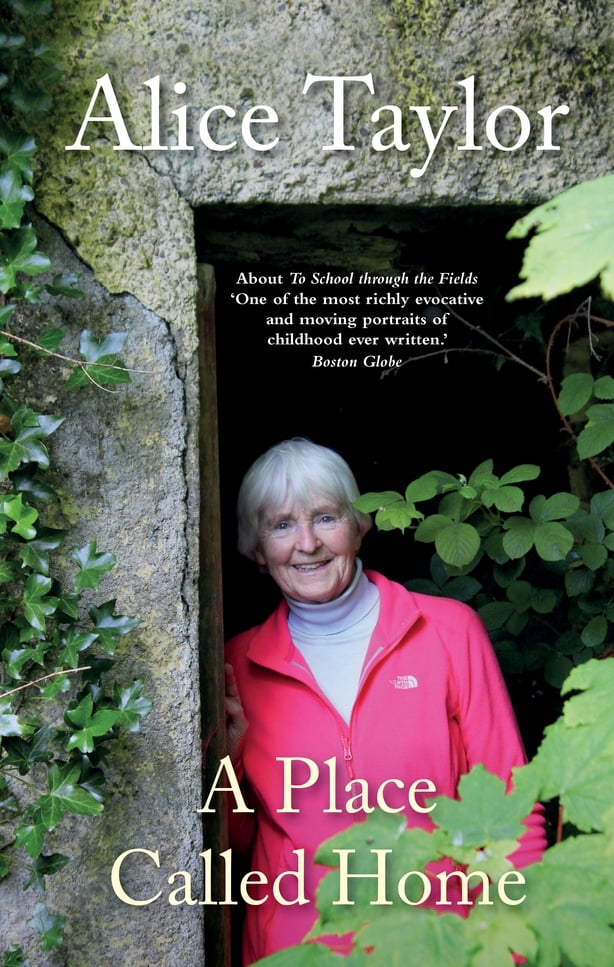

We present an extract from A Place Called Home, the latest book by celebrated author Alice Taylor.

For over sixty years, Alice Taylor has lived in the village of Innishannon. But her childhood was spent on a farm in north Cork, near the Kerry border, and her memories of that homeplace are vivid.

Here, she recalls the people and places from those days with her trademark warmth and wit.

From Cockcrow to Corncrake

The sounds and smells of childhood fade into faint prints on the back pages of our minds. But an evocative smell or sound can somersault us back into a memory gallery where we have pictures of the past filed away. People who grew up by the sea fondly remember its sound, and even the sad wail of the foghorn, now gone, is full of nostalgia for them. Likewise, for me the long-gone smells and sounds of the fields and farmyard are my deepest memories of my childhood home. Going back there now opens a memory gate into that forgotten world.

Leading from the garden into the big yard was a small gate which in later years I sketched from memory and had a replica made for my garden here in Innishannon. But whereas my gate is solely for remembrance and to keep me happy, the original was to keep the children safe inside it and the animals at bay outside. Back then we did not call the area inside that gate the 'garden’, but it was known as the ‘small yard’. Maybe we thought that gardens were for townies while our real garden was the land. We swung constantly off that old gate that bridged the adult gap between leisure and work. Its squeaking hinge also served the purpose of alerting us to unexpected visitors. Most of the neighbours came in through the surrounding groves or over the ditches, but those warranting a hurried, flustered inside tidy-up came in the gate. A glance out the kitchen window established if a ‘tidy-up visitor’ was approaching. However, when its squeaking became an irritant, my father oiled it silent, obliterating our substitute doorbell, until eventually the weather made its rusty voice audible again. When the Stations came around, the gate got a shiny new green coat, which sometimes a misplaced cow or calf succeeded in decorating before the big event arrived. Outside that little gate was the ‘big yard’, hedged in by an assortment of homes for an army of farm animals, all producing a variety of sounds, smells and endless jobs. Now, all the animal shelters and the endless jobs, and that small gate, are gone. But back then, that now-silent farmyard was a symphony of sound.

The first sound to break the morning silence was the dawn chorus, which usually went unheard by us humans unless my father happened to be up attending to a calving cow. Then, one night while I was up minding bonhams I heard it for the first time. It was an awe-inspiring concert, heralding the arrival of a new day. And with the dawn chorus came the cuckoo with his repetitive ‘cuckoo, cuckoo, cuckoo’ – which, with monotonous regularity, he repeated constantly throughout the day. Like a record with the needle stuck in the same groove he was the ongoing background chant of our summers.

But out in the henhouse another ear was listening and as the first streaks of dawn began to light up the sky he sprang into action. Our large white imperious Mr Cockerel, with his bright red crowning comb and long strong yellow legs announced, in strident tones, from his high henhouse perch, that another day was about to begin. His insistent, repeated ‘Cock-a-doodle-doo’ set off a whole menagerie of sound which continued all day, until finally, with the descending shades of darkness, he stopped and the rasping voice of the corncrake performing his evensong told us that it was time for sleep. Mr Cockerel was our morning call and the corncrake was the sound of the night.

Mr Cockerel’s early, imperious wake-up call caused his harem of hens to reluctantly ruffle their feathers and very slowly withdraw their heads from beneath their wings as they softly clucked themselves into the coming of a new day. Their enthusiasm for morning did not match the strident tones of their strutting, domineering male master. However, as they eased themselves off their high perches they emitted gentle cooing sounds of satisfied self-sufficiency. Their male master lacked their calm, serene approach to life. Still, they did express a whoop of victory later when they produced an egg and wished to announce its arrival. And all morning around the farmyard their triumphant calls announced their ongoing egg production. The hens believed in getting the job done early in the day and afterwards they relaxed around the yard emitting little cackles of satisfaction, as, with fluffed-out feathers and wings, they scratched for seeds of nourishment under briars and bushes. Occasionally taking time to rest, they sat with outspread wings, emitting comforting sounds of contentment. But with the approach of feeding time, they gathered in a cackling cluster around the garden gate and made their presence felt in a cacophony of demanding voices. They generously shared their mash and oats with the flocks of little birds who descended and ran in under and around their plumped-out plumage. Occasionally during the day their royal master took it upon himself to crow forth a ‘Cock-a-doodle-doo’ of domination, which his female harem ignored. His sole contribution to their world was his fertilisation of their eggs, which later led to the arrival of clutches of yellow chicks chirping around the yard behind their doting mothers. These mothers occasionally sat in the sun with outspread wings from beneath which their chicks peeped out with little chirps of contentment, a delicate, mothering, joyous sound.

That grove behind the house sheltered rows of busy beehives and to stand beside them at night, breathing in the essence of their honeycombs and listening to their murmuring hum, was to feel close to the heart of creation. Back then, that old farmyard was full of the sounds and smells of animals, but when I return there now and stand listening to the sound of silence it is mostly the distinctive ‘crake’ of the corncrake that echoes back through the decades.

A Place Called Home is published by Brandon Press