Dec 24, 2024

Oct 20,2024

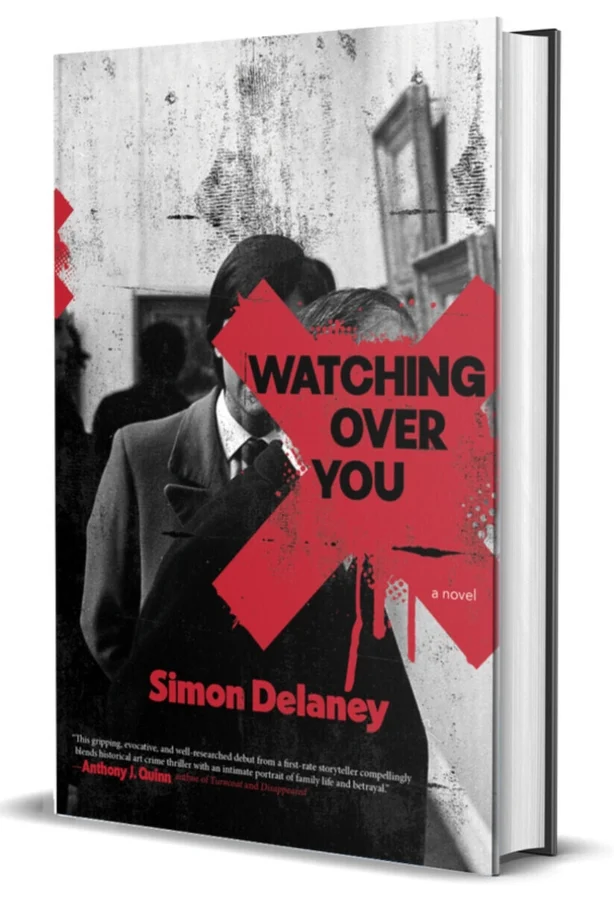

Alternating between London and Paris in the 1940s, the 1960s, and the present, Watching Over You explores the provenance of a collection of paintings hidden from the plundering Nazis during World War II and the fate of the families entangled in the search for the lost artworks...

Prologue: Paris, 1942

The two German soldiers dodged their way through the column of drab artillery vehicles that trundled along the Place de la Concorde. They did not slacken their pace as they climbed the short flight of steps at the Museum Jeu de Paume, a heavily fortified building on the banks of the Seine. The younger of the pair, but a military grade higher, Ronin Kohl had been close friends with his companion Karl Delitzsch long before they were paired together and put to work as part of a handpicked unit tasked with the removal of hundreds of precious works of art from locations that covered more than four countries. They had both been Hitler Youth, each had followed their father's footsteps into the party and, after meeting during basic training at the military academy in Dresden, had become inseparable as they progressed through officer training.

They saluted the sentry guarding the entrance and the double doors opened as if by their own volition. A passageway stretched before them, red-carpeted, flanked by two Roman statues and dimly lit by tall windows on either side. Beneath the gloomy ceiling of the room that had once been a tennis court for the seventeenth century nobility, lay rows and rows of gold-framed oil paintings, marble sculptures, and tapestries leaning against each other in the thick shadows. The place was deserted but the air itself seemed to vibrate with the dusky colors of the paintings. Ronin took quick steps and glanced behind at Karl whose spectacles glinted as his head swiveled left and right. His companion wore an expression of amazement, wonder, and pride.

Ronin could almost smell the power and opulence in the surroundings. It was a long way from the heavy fighting they’d both survived in Yugoslavia, Albania, and Greece. That guerrilla war still raged, and each had been lucky to come through it unscathed. And even luckier to have been reassigned to the newly formed Reichsleiter Rosenberg Institute for the Occupied Territories, or the ERR as it was more commonly known. Occupied Paris had its dangers, but it was like a holiday camp compared to what they’d been through in the last three years.

This morning their orders were to attend a briefing with their immediate superior, Bruno Lohse, who reported directly to Hermann Göring. Bruno Lohse was not a man to be trifled with. He was an art dealer but also a Nazi who had risen quickly through the party, and if he had a sense of humor, he kept it as well hidden as the treasures the Jewish population had squirrelled away. Today, Ronin and Kohl could hear almost every word he was shouting at the poor unfortunates currently in his office from outside in the corridor, despite the thick oak doors. He was in an even worse mood than normal. The Parisian Jews were not making it easy for him to do his job.

Lohse held daily gatherings with the heads of his various units of the ERR from 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m., in the offices he’d sequestered in the Museum Jeu de Paume. Waiting in that corridor was akin to waiting to see your dentist, only minus the fun, and the anesthetic.

Finally, as the door to his office opened, a number of German officers funneled out, clearly having been taken down a peg or two.

"What’s going on Walter?" Kohl said to one of the soldiers.

"He’s not his usual self," answered Walter, looking a little shaken.

"Why?" asked Delitzsch. "Someone spill coffee on his latest Matisse?"

"Not quite," replied Walter. "He just heard his brother has been killed in action, right after being sprung in a raid in Antwerp."

"S**t," said Kohl, looking at his partner.

"Maybe not the best time to ask for a raise then?"

"Get the f**k in here you two!" Lohse screamed from inside the office.

"Probably not," said Delitzsch quietly.

Lohse was standing with his back to them, looking out the window at the river Seine below. The officers stood to attention at the desk, waiting for him to speak. He said nothing, and they stood there for what felt like an eternity.

"Sorry to hear about your brother," said Kohl, breaking the silence after several awkward minutes.

"Don’t be," answered Lohse quietly, still facing away from the soldiers. "It was his own fault. He hadn’t studied the reconnaissance properly, walked straight into a trap." Finally, he turned. "Sit," he barked. "I have a pressing mission for you and your unit."

"Our favorite type," answered Delitzsch.

Lohse opened a file, sifted through some documents, and handed them to the two officers.

"We’ve had intelligence directing us towards a potentially ripe section of Le Marais," he said. Le Marais was Paris’s best-known Jewish neighborhood, a constant target for Lohse and his units since they’d arrived in Paris. "Within this specific area," he continued, laying out a street map of Paris on his desk and pointing to it with a well chewed pencil. "Our intelligence tells us that the lower section of Rue de Rosiers, between Rue Malher and Rue des Hospitalières St.-Gervais, was not sufficiently investigated. There are, according to our sources, several offices and homes that need to be revisited. Apparently, the Jews’ methods of hidings their valuables have improved significantly since our original sweep, which means we need to take a deeper look into these properties."

"When you say we, you mean us?" said Kohl flippantly.

His partner threw him a look as if to say, "Are you f**king crazy?"

Lohse didn’t acknowledge Kohl’s question.

"There are two buildings in particular I want you focus on," Lohse said as he handed the soldiers a piece of paper with an address written on it. "Wait until nightfall," he added. "That area still has pockets of active Resistance units operating, if you encounter them, don’t waste your time with arrests, just kill them." He paused and stared at them for a few seconds longer. "You have your orders. Now go."

Kohl and Delitzsch took the papers, stood, and saluted as Lohse lit a cigar and leaned back in his chair.

"Report back to me with a full inventory as soon as you have completed the order," he said as they turned to go. "Now I must telephone my mother and let her know there’ll be one less at the dinner table this Christmas."

In normal times Rue de Rosiers, or "street of the rosebuds," was a bustling stretch of activity, home to a large majority of the Jewish community in Paris and had all the trappings of such a hub. The focal point for the local community was the synagogue at number twenty-five, a place that would be packed during services, which, as result, meant the nearby falafel shop was the perfect place to pick up the latest gossip, as well as freshly baked treats.

Another feature of this avenue was the large communal bathhouse Hammam Saint Paul. In normal times, this schvitz would be populated by the leaders of the various local community groups three times a week, where they held council meetings, with grievances being both aired and resolved. These were not normal times though. A once bustling thoroughfare was now an abandoned, bullet-ridden, and desolate street. Those business and places of public gathering were now empty, destroyed. The majority of the people who filled them were gone; many would never be seen again. Most were sent on trains to Poland and other areas around Europe where their unsolicited destiny awaited. Others fled, to all corners of the world, grabbing what they could, and leaving before the Nazi hit squads kicked their doors down.

Kohl Delitzsch, and the rest of their four-man unit, made up of Hans Müller and Artur Weber, two lower-ranked but first-rate soldiers, passed the now defunct metro station on Rue de Rosiers not long after sundown. The street was effectively deserted, save for a few manned German checkpoints dotted along the length of the avenue. When the unit reached the nearest checkpoint just outside the Saint-Paul Metro, they were quickly waved through. The German soldiers had been alerted to the unit’s presence earlier that day, and this unit was afforded the same "access all areas" privileges that were normally reserved for members of the SS. Kohl and his men stopped momentarily to regroup by the entrance to the synagogue.

"Check the address again," Kohl said.

Müller pulled a piece of paper from his top pocket and read the details in a whisper, "Twenty-nine, thirty-three, and thirty-seven. All on the second floor of that block according to intelligence." He pointed down the street.

"Right," said Delitzsch. "Kohl and I will take the back stairs, you and Weber head up to the balcony and cover the front doors." He stared at Müller. "And not a f**king sound on approach, the Resistance still operates in this area."

The four-man squad headed down the avenue, splitting into two groups as they closed in on their target. Kohl started to climb the drainpipe to reach the second floor, Delitzsch kept watch.

"All clear," Kohl said as he reached the landing. Delitzsch headed up after him, and they surveyed the row of small windows facing them. "That one first," he said, pointing to the window farthest away from them.

They moved along the wall and got to the window, which was now just a broken frame, the glass having been blown out in an earlier raid. The two men entered the apartment through the broken window and were met in the hallway by Müller and Weber who had come in through the front door.

"Any problems?" asked Kohl as they started to make their way around the cramped two-bed apartment beginning their search.

"None," answered Weber. "There isn’t so much as a mouse in these buildings."

"It’s not mice I’m f**king worried about," replied Delitzsch as he pried open a door to a bedroom that had been blocked by rubble.

The apartment had already been destroyed, the infantry that had come before them had smashed their way through it, clearing out the families who were discovered hiding inside. Scattered across the space were the splintered remnants of tables and chairs, while once pristine but now torn curtains, framed the shattered windows. Delitzsch’s feet crunched their way through the broken glass as he moved quickly from room to room.

"What are we supposed to be looking for in here? The place has been looted already, cleaned out, no?" asked Müller as he stood and looked at the debris.

"F**k’s sake, Müller," said Kohl as he pushed past him in the hallway. "Utilize that dormant organ under your helmet for once in your life. Just because someone said it’s been done, doesn’t always mean it has."

Müller had an expression on his face resembling a dog that had just been shown a card trick. Kohl exhaled and pointed to the ceiling in the hallway above Müller. Relatively unmarked from the previous raid, the ceiling was painted white, but Kohl had noticed something—a sixty-centimeter square of faintly cracked paint.

"I’ll bet you two packs of cigarettes there’s a makeshift loft up there," Kohl said as Delitzsch realized what his partner had spotted. He quickly went to find something to stand on.

Delitzsch and Weber dragged a tattered table into the hall from the living room. Kohl climbed onto the furniture and, using the butt of his rifle, started to tap away at the cracked paint. It wasn’t long before not only the paint gave way, but the layers of plaster behind it too. Now covered in white dust, Kohl stood back slightly to reveal a square cut into the roof, with what looked like a hinge poking through the plaster at one end.

"See?" said Delitzsch, patting Müller on the shoulder. "That’s why he’s one of Göring’s golden boys. This bloodhound could sniff out a gem blindfolded, underwater, from three kilometers away."

After some more thumping with his rifle, Kohl pushed on the now released square hatch, and it opened, flapping back, and revealing the entrance to a hidden loft space. As the crew entered the space one by one, they soon realized they had hit pay dirt. Using their army issue lighters, they found pieces of cloth, fashioned them into makeshift wicks, and then using some old wine bottles they’d found below in the apartment, they soon had the entire room bathed in soft light. They were surrounded by chests, crates, suitcases, and strongboxes, all left behind by the unfortunate tenants, presumably with the hope that they would one day get back home to retrieve them.

The four-man crew started to work their way through the hoard. They pulled all sorts from the room, from notebooks and diaries, toys, and oddities, to small pieces of jewelry and ceramics, as well as the odd small painting and sculpture.

"This’ll get us a seat beside the Führer at the next convention," said Weber as they started to bundle everything into their backpacks.

"Only if any of this s**t is worth anything," replied Delitzsch. "And you're hardly an expert on the subject," he added as he wrapped another bundle of items and packed them away. "You couldn’t spell Botticelli, let alone recognize one."

The squad laughed, comfortable in each other’s company, even in these most bizarre of circumstances.

As Weber and Delitzsch handed their overfilled backpacks down to Kohl, who had moved back down to the landing, Delitzsch spotted something in the corner of the attic. Another crate, tucked under a table, that they’d earlier missed. He pulled it out, opened it, and revealed some paintings, varying in size, six in total.

"Another one!" he shouted to the men as he pulled it towards the attic entrance. He lowered the box slowly down to Kohl.

"Right, let’s wrap this up and f**k off," Delitzsch said.

They left through the front door of the apartment, their backpacks full, carrying two crates, one between two. Laden down, they were moving slowly when they reached the front of the building, emerging onto the first floor balcony that ran the length of the building. Kohl suddenly put his hand in the air, and snapped his fist closed, the sign to stop immediately. They stopped dead, and waited, watching their commander’s hand closely. Kohl flashed two fingers, touched his ear, and pointed forward, meaning he’d heard something ahead of them. He signaled the men to back up. As the four men inched backwards, he again closed his fist. They stopped. Kohl was now pointing behind them.

"What the f**k is going on?" whispered Weber.

"Shut the f**k up!" replied Kohl.

Just as he finished the sentence, a shot rang out, the bullet striking Weber in the center of his forehead, killing him instantly.

"MOVE!" shouted Delitzsch, and the three remaining men scrambled to take cover behind the low wall of the balcony.

A French Resistance sniper positioned on the roof opposite was now reloading and taking aim at the three remaining German soldiers. Kohl quickly looked around, assessing their options. The balcony had stairs at either end leading down to the street, and that looked like the only viable choice.

"On three, you and me head to that one," Kohl said to Müller. "You head to that end," he said to Delitzsch.

"F**king Resistance," Delitzsch muttered as he prepared to bolt for the stairs.

Kohl held up his right hand, and counted down with his fingers: three, two, one, and then go. Kohl and Müller headed to the right end of the balcony, and Delitzsch to the left. As Kohl reached the stairs, four members of the French Resistance were charging up the steps, fully armed, guns trained on the Germans, while at the other end of the balcony a similar scenario was facing Delitzsch.

"Back!" Kohl shouted at Müller, who was now running back towards the middle of the balcony with Kohl behind him. The sniper took aim and hit the balcony with two quick shots. The three German soldiers, now surrounded, were running out of options. As they reached each other in the middle of the balcony, Kohl shouted to Delitzsch, "Jump!" and instinctively both he and Delitzsch make a hard turn and jumped over the balcony and down fifteen feet onto the street, leaving Müller and the two crates behind.

As they hit street level, shots rang out as Kohl looked back up to see Müller being gunned down by the approaching Resistance fighters. Delitzsch pushed his partner down the road, and they started to run, shots peppering the walls around them as they darted through the narrow laneways surrounding the nearby synagogue. Eventually, they reached a German checkpoint, and safety.

The Resistance didn’t give chase. They knew they’d be outnumbered, and they’d had a good night, with two more Nazi occupier’s dead. They recovered the two crates the Germans had abandoned on the balcony and quickly headed for their own sanctuary, the nearest safe house, less than a kilometer away, on Rue Pavée.

On the way, the Resistance group, originally made up of twelve men, split up to avoid capture, and by the time they reached the disused warehouse only four members of the squad remained, carrying the two crates. The upstairs office was a small dark room, filled with cigarette smoke, where the primary source of the smoke, their squad leader, Eric Purdue, was waiting.

"Well?" he said to the returning unit. "How did it go? Was the information good?"

"Spot on my friend," said Robert Morel, the most senior of the four Resistance members there.

They put the two crates in the center of the room and started opening the first of them, removing the selfsame items that Kohl, Delitzsch, and the now deceased Weber and Müller had pulled from the makeshift attic some forty minutes earlier. Purdue started to go through the contents of the second crate.

"Well well," he pronounced as he pulled six paintings from the crate one by one. "What have we here?"

They all looked at the bounty, which was now spread out across a large table. Six paintings, from six different artists, all with different subject matters, some portraits, some landscapes, but all beautiful.

"Which house were these taken from?" Eric asked his comrades.

"We followed the German squad and watched them leave number thirty-three," answered Robert.

"And who lived there?" Eric asked.

Robert checked through a copy of the most recent census, which the Resistance had secured through a friendly official in the local council offices now controlled by the Nazis.

"Rothstein," said Robert. "A Mr. and Mrs. Rothstein. One daughter, Edsel."

"Do we know what happened to them?" asked Eric. Robert checked through some other documents that were laid out on the table, lists collated by Resistance members with the help of the few remaining locals in the area, providing knowledge on the area and, more importantly, details about the fate of the residents who had lived there.

Robert looked up from the list. "The mother and father were marked for Belsen," he said.

"And the daughter?" asked Eric.

Robert again went back to the list. "Smuggled out with a group of teenagers and younger children, presumably to northern Europe," he replied. Eric stood holding the smallest of the paintings in his hands, gazing upon it adoringly.

"Well, the Rothstein’s certainly have excellent taste," he said. "These paintings wouldn’t look out of place in the Louvre. We’d best try and get word to little Miss Edsel Rothstein, and let her know that we have located her parents’ possessions. I’m sure she’ll be glad to know they’re in safe hands now."

Watching Over You is published by Rare Bird Books