Dec 24, 2024

Oct 31,2024

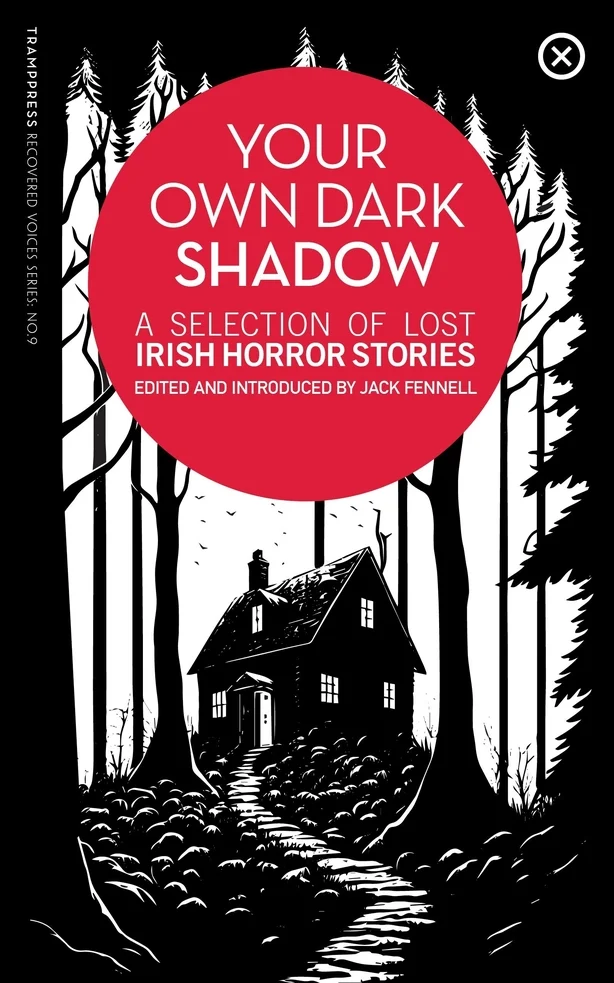

Especially for Halloween, we present a selection from the chilling new anthology Your Own Dark Shadow: A Selection of Irish Horror Stories.

Editor Jack Fennell introduces The Lamparagua (1897) by May Crommelin below...

Some of the scariest experiences come from realising that something we take for granted has hidden, dangerous depths. Our supposed separation from nature is an easy lie to believe in, until the ground underfoot turns out to be quicksand, or the log floating beside you in the river turns out to be a crocodile. The natural world, too often regarded as inert and subordinate to human will, has secrets that reveal themselves in horrifying ways, as in this feverish tale by May Crommelin, originally published in The Pall Mall Magazine in August 1897. Turn your back on the forest at your peril...

THE TWO MEN HAD HELD ON steadily riding since two hours before dawn, going all day without stopping, save for a brief noontide halt. During the afternoon of yesterday their track had lain across an utterly desolate pampa, therefore they had pushed on to reach cultivated country again, and water before nightfall. Now, towards evening, they found themselves near a long lake, bordered with reeds, the haunt of numberless wildfowl.

A small rocky valley, down which the active Chilean ponies weariedly scrambled, grew greener towards the lake shore, where a stream which the travellers had followed for some time widened into a V-shaped marsh.

'It's near sunset, Pedro. Let’s camp here for the night,’ said Ramsay, shivering slightly, for the fever had taken him two days ago. ‘Own the truth, man! You’ve lost your bearings, and don’t know whether we’re nine miles or nine leagues from the silver mine. Besides, the horses, poor beasts, will be dead beat.’

‘Of what good is a horse that cannot do his sixty miles when asked?’ returned the Chilean guide. ‘But, truly, the devil seems to have been driving round on these hills, changing their shapes since last I came this way.’

He gazed with discontent deepening on his features at the hills behind, hiding the sandy desert, far beyond which rose the mighty range of the Andes, still veiled in rosy haze this hot December evening. Then, in sudden recollection—

‘There’s a rich Englishman who lives near a lake in this neighbourhood. He has smelting works and a large estate. The house may be close at hand.’

‘Or it may be on the opposite shore,’ said Ramsay, wearily dismounting. ‘Hobble the horses, and let’s go up to yonder hilly ground jutting into the lake. Then if you can see signs of a hacienda, we’ll make a last push for it. If not, I rest.’

‘Why not, patrón?’ said the huaso (1), using the almost invariable courteous Chilean assent to assertions or requests.

Up among rocks and brushwood they climbed, till, advancing to the far crest of the hillock, they scanned the lake shores attentively. Northwards, at a mile’s distance, a wooded headland arrested their vision; south and west there was no human habitation in sight, though the ground here and there showed signs of cultivation and the pasture was good.

Right across the lake the sun was sinking gloriously red, against a background of the pale olive green and lilac hues seen so often in a Southern Pacific sky. Soothed by the spectacle, Ramsay sat down on a rock to rest and smoke; and with Indian impassibility Pedro did the same. All gringos were mad, he knew; if this one liked staring at nothing, he was more easily pleased than some other foreign lunatics. But presently Pedro became aware that there was something to be seen among the rocks below. Signing to Ramsay, both men peered stealthily past screening myrtle bushes and witnessed an evening domestic scene in animal life.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

The ground rose in two broken ledges from the marsh, and on the upper one a dog-fox and vixen were playing with their cubs near some crannies where was doubtless their home. Presently the mother left the rest, and stretched herself sleepily in the evening sunlight midway on the grass ledge. One cub followed to bite her neck, but, on being repulsed, returned to gambol with his brothers. As he watched them, Ramsay also noticed a low withered tree, standing in the marsh twenty yards below, alone, and partly submerged, with a hollow cleft in its side.

All at once the peon touched his master’s arm and pointed open-mouthed towards the vixen. She had risen as if in terror, both her head and brush curved towards the ledge. Then, while her four paws seemed firmly planted gripping the turf, she was drawn broadside some yards towards the edge by invisible means.

The other foxes, old and young, meantime disappeared in the twinkling of an eye into the rock crevices.

As both men eagerly gazed, the vixen’s tension relaxed. On the brink she recovered herself and standing still for three or four seconds, as if dazed after deadly effort, she turned tail and darted towards her lair. Two springs only – on the third she paused in mid-flight! Once more she resisted, but was dragged back towards the edge, this time tail foremost. At the same time a rush of wind sounded like a sh-h in the stillness. Ramsay knew now he had heard the same sound two minutes before, but had fancied it a light breeze among the leaves. Craning his neck forward, Jock believed he could see an agonised expression in the creature’s eyes, as against her will she slid inch by inch – over!

The fall was not great. A lower grassy terrace surmounted the marsh. Even as they whispered, the watchers saw the victim rise.

A second time – but feebly, like a mouse released from the deadly grip of a cat – the poor she-fox crawled away with drooping brush towards the sheltering rocks. Ramsay searched the marsh with a sportsman’s keen glance, to discover whether the creature had been lassoed by some invisible means, and where was the native hunter. Then he bounded to his feet and, pointing towards the withered tree, his arm stiffened with amazement, exclaimed, ‘Look!’

The cleft in the tree-trunk was visibly widening and gaping, till it looked like a hideous bark-lipped mouth that was drawing a long inspiration. Again there came the same sound in the air, and the vixen, curled in a helpless quivering ball, was borne five yards, as on a windblast, disappearing right into the hollow of the tree.

The withered wooden lips contracted over the creature’s living head; two dead branches above stirred slightly, like antennae; the cleft closed, leaving a jagged scar in the tree-trunk. That was all.

The scene was still and peaceful as before. A flight of wild duck circled twice over the lake and then alighted on the surface with distant quacks. Behind in a fuchsia thicket a native thrush was singing. The tree was immovable.

Wondering if he could be dreaming, Ramsay turned to the peon. Pedro had turned pale, and he was shivering.

‘The Lamparagua! Fly!’ he gasped, with a cry of horror, and plunged downwards among the rocks. Jock overtook him just as the huaso leaped bare-backed on his horse.

‘Stay for me, my lad, at the valley head in safety. I’ll not leave the saddles and blankets,’ said the Scotsman coolly. But his own breath fluttered in his throat, more than from the run, and while his hands tugged at strap and buckle, his head turned to glance at the tree that remained motionless in the distance.

Rejoining Pedro, who waited half a mile away, the master found the peon on his knees, crossing himself and gabbling over and over every scrap of the Latin prayers he could remember, which the padres had taught him in boyhood. They were few, and he mixed them so ludicrously that his listener almost laughed. ‘Holy Santa Rosa – miserable sinner!’ ended Pedro, rising and saddling up with remarkable haste while throwing off some last proclamations of this rare excess of piety. ‘It was a witch, señor; the country is full of spirits. Holy Saint Peter, I ducked your image last autumn in the sea. Forgive! Those fishermen are such blasphemers, and rail against you at the first bad weather. I abjure all evil-livers, holy—’ An awful oath followed as the pony swerved. Pedro stuck his huge rowels in the beast’s flanks and cantered furiously away, his poncho filling with air as he worked his arms like a windmill’s sails, shouting, ‘Ride, ride, patrón! Leave this God-forsaken country, quick!’

‘Aye, if only our horses can travel,’ muttered the Scotsman. True enough, the tired beasts soon showed that they could not be roused long beyond an ambling motion, not unlike the gait of a Peruvian pacer; but which, when unbroken all day, may cover a great distance before nightfall. Not till they had gone some miles could Ramsay persuade his terror-stricken guide to talk sensibly. ‘What is this beast-tree? Lamparagua (2), you called it. Does it exist elsewhere in Chile?’

‘Who knows, señor? I only heard of such rare trees as northern witches from a rough roto (3) who came from this country. I remember it was one evening in July, ten years ago, as we sat in a circle on the ground round the brasier. We thought he was improvising a tale, as we had in turn improvised or recited songs and legends – telling lies for fun, as the patrón may know is our custom. There was naught more I can call to mind, save that they swallowed animals and lived near marshy places. Saints preserve us! Ride on to the mines. Stop here? Never!’

Ramsay dared not lose sight of the man. At least Pedro knew something of the country. He might strike their right track soon. So the soft twilight of the south drew round them, as they rode wearily. And the night came, black and moonless, as they bent in their saddles, more weary yet. The reins lay loose on the horses’ necks now, Pedro trusting to the animals’ instinct; for ‘the good land’ could not be far where men lived, and there were home- steads and supper and provender.

When midnight was past, Ramsay felt his strength going from him. By the faint starlight they had just plashed through a gravelly stream, in which the horses stopped to drink before reluctantly stumbling up the far bank, where their hoofs struck muffled on grass.

‘Pedro, I can hold up no longer,’ called the engineer feebly, reeling in his saddle, as an ague fit shook him like a rigor. ‘Leave me, if you will. I must lie down.’

Guessing by his master’s voice that the latter must be very ill, the peon hastily came to Ramsay’s help in dismounting, then guided him to the shelter of some bushes that were faintly discernible. Here he placed a saddle under the sufferer’s head, and laid a blanket over him.

Not far off there was a small grove of shrubs, darker than the surrounding twilight, beside which rose a big tree with a huge bulbous base and exposed roots like those of a cotton tree. Near this Ramsay’s horse strayed, cropping the grass; so Pedro, following, tethered him to one of these roots, which he had discovered by stumbling against them in the blackness.

‘Caramba!’ he muttered. ‘Stay there; animal not to be trusted.’ His own beast knew him, and never went far from its owner’s side.

Then the guide sat down beside his exhausted patron, who slept for fevered snatches, or woke to ramble in delirious talk. So the time passed till the faint light strengthened.

All at once, Ramsay fancied he heard Pedro’s voice crying out in a tone of desperation – or was it terror? – ‘Me voy! I’m off to bring you help!’

The sick man did not heed, though vaguely conscious he was left alone. It seemed to him that he was in a hospital. The doctor would come round presently; if not, it was peaceful to lie still. Was that his mother, lifting the hair on his fevered brow?

Then he started awake as a horrid cry roused his dulled ears. It was the scream of a horse!

What was this well-known valley? Where was he? For, raising himself weakly on one elbow, Ramsay saw a stream running past rocks which were strangely familiar – and yet when had he seen them? The river emptied itself in marshy land. The dawn showed a dark grey surface beyond, like a sea ... or lake.

With a cold terror, the sick man recognised that he lay not two hundred yards from the marsh of the Lamparagua: that headland; the water! All night they must have ridden in a circle!

The horrible scream was already fading from his sick memory like a dream, when a snorting and scuffling noise caused Ramsay to turn slowly his weak head. He saw his horse stamping, pulling back from its halter, and with distended eyeballs staring terrified at a tree, to a root of which it was fastened. What was wrong? The tree had two bare topmost branches like horns, and some lower ones also without leaves, yet this was summertime; in December... It was withered! And, there above its onion-shaped bole was, surely, a dark scar, a crack! Oh, horror! The top of the tree was that of the Lamparagua, in the marsh. And now, as Jock stared with fever-weakened eyes through the dim daybreak, the lower branches moved slowly downwards, clutching the horse’s halter with claw-like twigs; the crack in the side of the Thing was wid- ening. Again a fearful sound woke the sleeping glen: the horse’s cry of terror. Jock tried instinctively to find his revolver, but his senses reeled as the tree aperture gaped, opening upwards. The horse was drawn towards it – nearer! – fighting, struggling. Then two shots rang out, and a man fainted, and knew no more.

When Jock Ramsay came to himself, the sun was high in the heavens. He was sheltered by wild myrtle from its heat, and though very weak, his senses had come back. Memory was slower. Ah – he remembered! Opening his eyes in a wide stare of apprehension, Ramsay saw himself lying alone. There was a thicket near, but not the awful tree. Pedro was gone; so were the horses. But perhaps – perhaps – that last vision of the Thing engulfing the poor roan cob had been a nightmare, a fevered frenzy. Feebly reconnoitring the ground, the sick man noticed that he lay on a grassy slope between the stream and the rocks where the foxes lived: a small cape. Behind his head, the ground must be open farther up the valley. There lay safety, away from the horrible marsh and the Lamparagua, if there were such a tree indeed. Surely it had all been a hideous dream. Drawing the myrtle leaves aside, as one might a curtain, Jock feebly turned himself to examine the glen. Then his fingers clenched, his breath stopped, and a thrill of horror froze his spine. The Tree was there! Out in the open, on the grass, with not a bush near it, right between himself and safety.

Take it quietly! For manhood’s sake, think out this business, and don’t turn faint like a schoolgirl seeing a snake. First, was the whole affair a dream? Was that withered tree out yonder on the sward the very Lamparagua? For if so, there were several, or it could change its situation. It was neither in the marsh, nor by the fuchsia thicket. It ... O God!

For, as he peered, Ramsay believed that the tree was moving. It was horribly near, and it was surely creeping forward by inches. He held his breath, and marked a grass tuft at its bulbous base.

Now... now it had passed beyond the tall silvery grass plumes and spear-leaves, and was close by a stone... was stealthily rounding it. Yes, the Thing was approaching him; doubtless it had stayed quiet till now, gorged with its morning meal, but it was slowly nearing its next victim. With eyes fascinated by fear, Ramsay saw its roots moving forward like giant knotty suckers that gripped and held fast in the herbage, noiselessly moving with the motion of a tortoise.

The hair of the young man’s flesh stood up; an icy coldness numbed his blood. Then with a strong effort he gathered his senses to think out an escape. The rocks ahead were his only chance.

There among the crannies, where the foxes had their dens and hid in safety, he could hide. But he could not rise! His head was dizzy with fever; his strength was as running water; his legs and feet seemed not his own, mere useless weights to be dragged on by sheer pluck. For he had already started—

Grasping the myrtle stems to give himself an impetus, Ramsay was crawling away towards the rocks, foot by foot. He lay outspread like a lizard, for his only strength remained in his arms and chest. Inch by inch, he crept onward as fast as he could go, clutching at the grass tufts, at the sage-bushes, drops of perspiration running down his face.

Faster, faster, if it could only be done! The man had covered some yards; surely the tree moved more slowly. Ah!

A blast blew backwards over Ramsay’s head, raising his hair. By instinct he dug his nails into the ground, flattening his body as much as he possibly could. The indraught was as if air had rushed by into a deep cavity, while a sound like that of an escape pipe hissed in the air. Then it was over.

As drowning men are said to see a thousand past scenes in a few moments, so in an agonisingly lucid flash Jock Ramsay reviewed his life. Then he recalled yester-evening, how the wretched fox had gotten breathing-time twice, as once he had now. How long would this horrible game last? The beast-tree was paralysing the human being: he thought of a snake fascinating a rabbit.

Slowly, more feebly, the victim still crawled. Why did that second blast not follow? Could the Lamparagua be so near, it needed no aid beyond that of its cruel hooked branches? He must see!

Turning his head, as he still dragged himself onward, the fever-stricken wretch beheld a strange sight. He had left his blanket behind upon the ground when first making his escape, and it was now wrapped round the tree-bole, as if the Lamparagua had failed to suck it in, and was wrestling with this unknown prey, both branches holding it fast outspread on claw-like twigs. It was a respite! A few seconds more of air, light, life!

Yes, the beast-tree was standing still; yet it had covered more ground than its hunted prey, during the time both had moved. Ramsay felt for the revolver in his pocket. There was one bullet left, he knew, and if escape were hopeless, then—

At last! The rocks were near. The man began scrambling painfully up a steep incline of loose earth and rounded stones which resembled a moraine, and that gave no hold to his desperate grasp. Looking up, he saw with hopeless eyes that there had been a slight landslip lately, which had left the bank projecting over- head, so that he could not reach the top; looking down, that the Lamparagua was slowly but steadily approaching once more over the grass, foot-root following foot-root. There was a torn piece of crimson blanket hanging on one bough.

He must struggle across the face of this treacherous slide to where a clump of yuccas were smouldering, their stems blackened as one often sees them, whether from spontaneous combustion or sun-fired in some inexplicable manner, no man knows.

Fire! The smoking plants suggested a thought to the man. He stayed still, holding on half-way up the scree. He felt for his matchbox; there were two matches left.

Then Ramsay, instead of longer seeking escape upwards, flung himself in still more desperate eagerness down the steep slope again towards his enemy. He was at bay.

Where the grass began, the man stopped and stooped, pluck- ing dry blades and twigs with the haste of one who has but a few moments to live should this plan fail of success. Not a drop of rain had fallen since October; the scorching summer heat had burnt the grass to tinder. There came the spurt of a match.

Two moments... five!

The fire-spark, kindling, seemed about to spread, when a roar- ing wind-gust through the valley’s stillness blew it out, and the man felt himself sucked irresistibly towards a clump of prickly pear, to which he clung palpitating, with his face pressed against the thorny broad discs that tore the skin to bleeding. Ah! That was over!

For the last time one chance was left – one match! Again Ramsay snatched what dry fuel lay within his grasp, as he sheltered beneath the bushes. His papers, cheque-book, all were in a small valise he had instinctively thrust overnight under his saddle-pillow. There was one letter left in his breast pocket, which he had carried there two years – the last one ever written by his mother. He tore it out.

With shaking fingers, and blinded by blood-drops he dared not wait to wipe from his eyes – knowing the while that the Lamparagua was stalking a yard nearer at each motion – its victim carefully struck the match. Sheltering the tiny flame with one hand, he turned the wax-stem gently till it lit. Next the letter; and the fire licked the words ‘My dearest Son,’ then blazed and crackled in the funeral pyre of broken bramble and dried myrtle leaves that burnt a dead woman’s last token of love to her young- est born. Gladly would she have known it sacrificed on the slight chance to save his life! Ramsay thrust both hands deep into the burning mass, and recovering strength in the excitement of hope, he staggered towards some clumps of tall grass of the pampas a few feet away. The sparks fell, making a trail as he went that caught the dry herbage. Hurrah! How the giant grass-stems took fire, blazing high in a glorious bonfire!

A hasty glance over his shoulder. The Lamparagua was not twelve yards distant; its jaws were widening. But the fire-wall was between them.

There came a rush of wind ending in a sound more fierce than a wounded lion’s roar. The man was caught by the blast as he stood upright, weak yet defiant, matching his puny being against the strength of the brute-tree with the help of the mind within him controlling the fiery element as a weapon. Sucked forward, blinded by smoke, scorched, Ramsay fell on his face and lay still with a last conscious effort to save his life. Beyond his body the myrtles and fuchsias were crackling, the tall chajual blossoms blazed like high torches, the fire was spreading, leaping up to the boldo branches in yonder thicket, running over the open ground in a low sheet that burnt the Lamparagua roots.

For half a minute the Thing stayed, trying to stand its ground. Now it was in full flight! The great sucker-feet were travelling over the burning herbage, dragging its tree-trunk with agonised efforts, yard upon yard, towards the stream.

Five minutes later, there came a galloping of horses down the valley, and men’s shouts. But Ramsay did not hear them. He seemed to lie prone at death’s door, too weak to enter unless spirit hands lifted him over its threshold and brought him within to be at peace and rest.

But they were earthly hands that were now trying to pour some brandy down Ramsay’s throat. When his eyes opened, Pedro was supporting his master’s head, while a group of men around were watching the stranger curiously, foremost among whom was an English gentleman.

‘Coming to all right?’ said the latter. ‘A near shave that. You began to smoke, I take it, finding yourself pretty nearly lost and famished, so the valley got fired. We have been out searching for you since morning, when your man rode up to my hacienda, worn out and demented. We passed the head of the valley at ten o’clock, but could see no sign of your horse, which Pedro said he had tied to a tree. What’s the matter?’

For Ramsay struggled up, and was staring round.

‘The tree! It was out there before the fire: Pedro – you know!

Where is it gone?

Pedro only shivered and stared. Some of the other peones, muttering, and giving sidelong glances at each other, crossed the burnt ground looking about them.

One saw a partly submerged tree at some distance downstream, floating slowly into the marsh. His attention was caught by a gleam of something scarlet tangled in the topmost withered bough.

A few days later, Ramsay was stretched at ease in a cane deck-chair, with a tall glass of iced drink in the wicker socket by his arm. Overhead a veranda was shaded with masses of roses, stephanotis and bignonia. Sunshine flooded the garden stretching beyond like a dream of enchantment, where tall palms shot above high flowering trees, and oranges and lemons were mingled lower with gardenias and poinsettias.

Jock had just finished after talking for some twenty minutes, so felt thirsty, exhausted, and excited.

‘That’s the whole story,’ he ended. ‘Now, do you believe me, Mr Campbell? Till now, I fancy you thought me mad.’

‘No, but possibly a bit delirious in your fever, so that you imagined some tale Pedro told you of the Lamparagua had really happened to yourself. That was all,’ said the kindly host.

‘Man alive! There is Pedro to witness also. And where is my horse? And your own lad saw the torn red blanket in the marsh!’ cried Ramsay.

‘True, quite true,’ nodded Campbell, coolly reflecting. ‘Well, my dear fellow, if it is any satisfaction to you, I do believe you are one of the few living human beings who have seen the Lamparagua. What is more, for some years back I have heard rumours of such a thing, and that it haunted this lake and another adjoining it, both on my estate. But, to confess the truth, I fancied the story was a convenient legend of my cattle-herds to account for missing beasts. Yes, I believe. But hardly anyone else will, even in Chile. Of course the peones know. They are nearer Nature than we.’

NOTES

(1) A Chilean horseman and herdsman, analogous to an American cowboy.

(2) Author’s note, literally, Lamp of the Water: a kind of will-o’-the-wisp.

(3) From the Spanish for broken, vulgar or lower class; sometimes used as a derogatory term for Chileans.

Your Own Dark Shadow: A Selection of Irish Horror Stories is published by Tramp Press

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: MAY CROMMELIN (1850–1930) or Maria Henrietta de la Cherois Crommelin in full, was born at Carrowdore Castle in County Down, into a family of Huguenot descent. Her first novel, Queenie, was published in 1874, and her writing proved popular enough for her to earn a decent living from it. She was well-travelled, and much of her writing was informed by her journeys through South America, the West Indies and North Africa; in addition to her fiction, she was a prolific non-fiction travel writer. During World War I, she worked in three London hospitals, and assisted Belgian refugees following the invasion of Belgium in 1914.